Michelle Pollock, Ricardo M Fernandes, Lorne A Becker, Dawid Pieper, Lisa Hartling

Key Points:

- Cochrane Overviews of Reviews (Overviews) use explicit and systematic methods to search for and identify multiple systematic reviews on related research questions in the same topic area for the purpose of extracting and analysing their results across important outcomes.

- Overviews are similar to reviews of interventions, but the unit of searching, inclusion and data analysis is the systematic review rather than the primary study.

- Overviews can describe the current body of systematic review evidence on a topic of interest, or they can address a new review question that wasn’t a focus in the included systematic reviews.

- Overviews can present outcome data exactly as they appear in the included systematic reviews, or they can re-analyse the systematic review outcome data in a way that differs from the analyses conducted in the systematic reviews.

- Prior to conducting an Overview, authors should ensure that the Overview format is the best fit for their review question and that they are prepared to address diverse methodological challenges they are likely to encounter.

This chapter should be cited as: Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews [last updated August 2023]. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5. Cochrane, 2024. Available from cochrane.org/handbook.

V.1 Introduction

Systematic reviews became commonplace partly because of the rapidly increasing number of primary research studies. In turn, the rapidly increasing number of systematic reviews have led many to perform reviews of these reviews. Variously known as ‘overviews’, ‘umbrella reviews’, ‘reviews of reviews’ and ‘meta-reviews’, attempts have been made to formalize the methodology for these pieces of work. Overviews are an increasingly popular form of evidence synthesis, as they aim to provide ‘user-friendly’ summaries of the breadth of research relevant to a decision without decision makers needing to assimilate the results of multiple systematic reviews themselves (Hartling et al 2012). Overviews are often broader in scope than any individual systematic review, meaning that they can examine a broad range of treatment options in ways that can be aligned with the choices that decision makers often make. In comparison to the length of time and resources required to address similar questions from a synthesis of primary studies, Overviews can also be conducted more quickly (Caird et al 2015).

In this chapter we describe the particular type of review of reviews that appears in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR): the Cochrane Overview. The chapter begins by discussing the definition and characteristics of Cochrane Overviews. It then presents information designed to help Cochrane authors determine whether the Overview format is a good fit for their research question and the nature of the available research evidence. The bulk of the chapter provides methodological guidance for conducting each stage of the Overview process. We conclude by discussing format and reporting guidelines for Cochrane Overviews, and guidance for updating Overviews.

V.2 What is a Cochrane Overview of Reviews?

V.2.1 Definition of a Cochrane Overview

Cochrane Overviews of Reviews (Cochrane Overviews) use explicit and systematic methods to search for and identify multiple systematic reviews on related research questions in the same topic area for the purpose of extracting and analysing their results across important outcomes. Thus, the unit of searching, inclusion and data analysis is the systematic review. Cochrane Overviews are typically conducted to answer questions related to the prevention or treatment of various disorders (i.e. questions about healthcare interventions). They can search for and include Cochrane Reviews of interventions and systematic reviews published outside of Cochrane (i.e. non-Cochrane systematic reviews). The target audience for Cochrane Overviews is healthcare decision makers; this includes healthcare providers, policy makers, researchers, funding agencies, informed patients and caregivers, and/or other informed consumers (Cochrane Editorial Unit 2015).

V.2.2 Components of a Cochrane Overview

Cochrane Overviews should contain five components (modified from Pollock et al (2016)).

- They should contain a clearly formulated objective designed to answer a specific research question, typically about a healthcare intervention.

- They should intend to search for and include only systematic reviews (with or without meta-analyses).

- They should use explicit and reproducible methods to identify multiple systematic reviews that meet the Overview’s inclusion criteria and assess the quality/risk of bias of these systematic reviews.

- They should intend to collect, analyse and present the following data from included systematic reviews: descriptive characteristics of the systematic reviews and their included primary studies; risk of bias of primary studies; quantitative outcome data (i.e. narratively reported study-level data and/or meta-analysed data); and certainty of evidence for pre-defined, clinically important outcomes (i.e. GRADE assessments).

- They should discuss findings as they relate to the purpose, objective(s) and specific research question(s) of the overview, including: a summary of main results, overall completeness and applicability of evidence, quality of evidence, potential biases in the overview process, and agreements and/or disagreements with other studies and/or reviews.

See Section V.4 for additional detail about each of these components.

V.2.3 Types of research questions addressed by a Cochrane Overview

Cochrane Overviews often address research questions that are broader in scope than those examined in individual systematic reviews. Cochrane Overviews can address five different types of questions related to healthcare interventions. Specifically, they can summarize evidence from two or more systematic reviews:

- of different interventions for the same condition or population;

- that address different approaches to applying the same intervention for the same condition or population;

- of the same intervention for different conditions or populations;

- about adverse effects of an intervention for one or more conditions or populations; or

- of the same intervention for the same condition or population, where different outcomes or time points are addressed in different systematic reviews.

Table V.2.a gives examples of, and additional information about, these five types of questions. Note that a Cochrane Overview may restrict its attention to a subset of the evidence included in the systematic reviews identified. For example, an Overview question may be restricted to children only, and some relevant systematic reviews may include primary studies conducted in both children and adults. In this case, the Overview authors may choose to assess each systematic review’s primary studies against the Overview’s inclusion criteria and include only those primary studies (or subsets of studies) that were conducted in children.

Table V.2.a Types of research questions about healthcare interventions that are suitable for publication as a Cochrane Overview*

|

Type of research question |

Examples of Overviews |

Comments |

|

Examine evidence from two or more systematic reviews of different interventions for the same condition or population. |

Pain management for women in labour: an overview of systematic reviews (Jones 2012). An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes ((Flodgren et al 2011)). Interventions for fatigue and weight loss in adults with advanced progressive illness (Payne et al 2012) |

This is the most common question addressed by Cochrane Overviews. |

|

Examine evidence from two or more systematic reviews that address different approaches to application of the same intervention for the same condition or population. |

Sumatriptan (all routes of administration) for acute migraine attacks in adults - overview of Cochrane reviews (Derry et al 2014). |

This question is often suitable for publication as a Cochrane Overview. This type of question may be most applicable to drug interventions, where differences in dosage, timing, frequency, route of administration, duration, or number of courses administered are addressed in separate systematic reviews. |

|

Examine evidence from two or more systematic reviews of the same intervention for different conditions or populations. |

Interventions to improve safe and effective medicines use by consumers: an overview of systematic reviews (Ryan et al 2014). Neuraxial blockade for the prevention of postoperative mortality and major morbidity: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews (Guay et al 2014) |

This question is often suitable for publication as a Cochrane Overview. This type of question examines the efficacy and/or safety of the same or similar interventions across different conditions or populations. |

|

Examine evidence about adverse effects of an intervention from two or more systematic reviews of use of an intervention for one or more conditions or populations. |

Safety of regular formoterol or salmeterol in children with asthma: an overview of Cochrane reviews (Cates et al 2012) Adverse events associated with single-dose oral analgesics for acute postoperative pain in adults - an overview of Cochrane reviews (Moore et al 2014) |

This question is uncommon but sometimes suitable for publication as a Cochrane Overview. This type of question may help identify and characterize the occurrence of rare events.† |

|

Examine evidence from two or more systematic reviews of the same intervention for the same condition or population, where different outcomes or time points are addressed in different systematic reviews. |

The CDSR does not currently contain an example of this type of Overview. |

Cochrane Reviews of interventions should include all outcomes that are important to decision makers. However, different outcomes may sometimes be reported in different systematic reviews. Thus, this type of question is uncommon but may sometimes be suitable for publication as a Cochrane Overview. |

|

* Overview authors may find other uses for Overviews that are different from those described above. † Authors must be careful to avoid making inappropriate ‘informal’ indirect comparisons across the different interventions (see Section V.4.1). |

||

V.3 When should a Cochrane Overview of Reviews be conducted?

V.3.1 When not to conduct a Cochrane Overview

There are several instances where authors should not conduct a Cochrane Overview. Overviews do not aim to:

- repeat or update the searches or eligibility assessment of the included systematic reviews;

- conduct a study-level search for primary studies not included in any systematic review;

- conduct a new systematic review within the Overview;

- use systematic reviews as a starting point to locate relevant studies with the intent of then extracting and analysing data from the primary studies (this would be considered a systematic review, or an update of a systematic review, and not an Overview);

- search for and include narrative reviews, textbook chapters, government reports, clinical practice guidelines, or any other summary reports that do not meet their pre-defined definition of a systematic review;

- extract and present just the conclusions of the included systematic reviews (instead, actual outcome data – narratively reported study-level data and/or meta-analysed data – should be extracted and analysed, and Overview authors are encouraged to interpret these outcome data themselves, in light of the Overview’s research questions and objectives);

- present detailed outcome data for primary studies not included in any included systematic review; or

- conduct network meta-analyses (see Section V.3.2).

V.3.2 Choosing between a Cochrane Overview and a Cochrane Reviews of interventions

The primary reason for conducting Cochrane Overviews is that using systematic reviews as the unit of searching, inclusion, and data analysis allows authors to address research questions that are broader in scope than those examined in individual systematic reviews (also see Section V.2.3). However, some research questions that can be addressed by conducting an Overview may also be addressed by conducting a systematic review of primary studies. Reviewing the primary study literature may be preferred in these cases because more information will likely be available. However, the resources required to conduct a full systematic review of all relevant primary studies may not always be available, especially when time is short and the research questions are broad. Thus, a second reason for conducting a Cochrane Overview is that they may be associated with time and resource savings, since the component systematic reviews have already been conducted. A third reason for conducting a Cochrane Overview is in cases where it is important to understand the diversity present in the extant systematic review literature.

Alternatively, it is preferable to conduct a Cochrane Review of interventions if authors anticipate the need to conduct searches for primary studies (i.e. many relevant primary studies are not included in systematic reviews) or to extract data directly from primary studies (i.e. the anticipated analyses cannot be conducted on the basis of information provided in the systematic reviews). Using primary studies as the unit of searching, inclusion and data analysis allows authors to extract all data of interest directly from the primary studies and to report these data in a standardized way. It is also preferable to conduct a Cochrane Review of interventions if authors wish to conduct network meta-analyses, which allow authors to rank order interventions and determine which work ‘best’. The rationale is explained in detail in Chapter 11.

In order to decide whether or not conducting a Cochrane Overview is appropriate for the research question(s) of interest, authors of Cochrane Overviews will require some knowledge of the existing systematic reviews. Therefore, authors should conduct a preliminary search of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) to gain a general idea of the amount and nature of the available Cochrane evidence. Authors with content expertise may already possess this knowledge. Overview authors should recognize that there will be some heterogeneity in the included systematic reviews and should consider whether or not the extent and nature of the heterogeneity precludes the utility of the Overview. Authors may find it helpful to consider whether:

- the systematic reviews are, or are likely to be, sufficiently up-to-date;

- the systematic reviews are, or are likely to be, sufficiently homogeneous in terms of their populations, interventions, comparators, and/or outcome measures (i.e. such that it would make sense from the end-user’s perspective that the individual systematic reviews were presented in a single product);

- the systematic reviews are, or are likely to be, sufficiently homogeneous in terms of what and how outcome data are presented (such that they provide a useful resource for healthcare decision making);

- the amount and type of outcome data presented is, or is likely to be, sufficient to inform the Overview’s research question and/or objectives; and

- the systematic reviews are, or are likely to be, of sufficiently low risk of bias or high methodological quality (i.e. authors should have reasonable confidence that results can be believed or that estimates of effect are near the true values for outcomes, see Chapter 7, Section 7.1.1).

V.4 Methods for conducting a Cochrane Overview of Reviews

Overview methods evolved from systematic review methods, which have well-established standards of conduct to ensure rigour, validity and reliability of results. However, because the unit of searching, inclusion and data extraction is the systematic review (and not the primary study), methods for conducting Overviews and systematic reviews necessarily differ. The key differences between the methods used to conduct these two types of knowledge syntheses are summarized in Table V.4.a. Methods for conducting Cochrane Overviews are described in detail in the sections below. When conducting an Overview, it is highly desirable that screening and inclusion, methodological quality/risk of bias assessments, and data extraction be conducted independently by two reviewers, with a process in place for resolving discrepancies. This is in line with the current methodological expectations for Cochrane Reviews of interventions (see Chapter 5, Section 5.6). All methods for conducting the Overview should be considered in advance and detailed in a protocol.

Table V.4.a Comparison of methods between Cochrane Overviews of Reviews and Cochrane Reviews of interventions

|

Cochrane Reviews of interventions |

Cochrane Overviews of Reviews |

|

|

Objective |

To summarize evidence from primary studies examining effects of interventions. |

To summarize evidence from systematic reviews examining effects of interventions. |

|

Selection criteria |

Describe clinical and methodological inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study design of interest is the primary study. |

Describe clinical and methodological inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study design of interest is the systematic review. |

|

Search |

Comprehensive search for relevant primary studies. |

Comprehensive search for relevant systematic reviews. |

|

Inclusion |

Include all primary studies that fulfil eligibility criteria. |

Include all systematic reviews that fulfil eligibility criteria. |

|

Assessment of methodological quality/risk of bias* |

Assess risk of bias of included primary studies. |

Assess methodological quality/risk of bias of included systematic reviews. Also report risk of bias assessments for primary studies contained within included systematic reviews. |

|

Data collection |

From included primary studies. |

From included systematic reviews. |

|

Analysis |

Synthesize results across included primary studies for each important outcome using meta-analyses, network meta-analyses, and/or narrative summaries. |

Summarize and/or re-analyse outcome data that are contained within included systematic reviews. |

|

Certainty of evidence (e.g. GRADE) |

Assess certainty of evidence across analyses of primary studies for each important outcome. |

Report the assessments presented in systematic reviews, if possible. Otherwise, consider assessing certainty of evidence using data reported in systematic reviews. |

|

* Methodological quality refers to critical appraisal of a study or systematic review and the extent to which study authors conducted and reported their research to the highest possible standard. Bias refers to systematic deviation of results or inferences from the truth. These deviations can occur as a result of flaws in design, conduct, analysis, and/or reporting. It is not always possible to know whether an estimate is biased even if there is a flaw in the study; further, it is difficult to quantify and at times to predict the direction of bias. For these reasons, reviewers refer to ‘risk of bias’ (Chapter 8). |

||

V.4.1 A note regarding important methodological limitations of Cochrane Overviews

Although Overviews often present evidence from two or more systematic reviews of different interventions for the same condition or population, they should rarely be used to draw inferences about the comparative effectiveness of multiple interventions. This means that they should not directly compare interventions that have been examined in different systematic reviews with the intent of determining which intervention works ‘best’ or which intervention is ‘safest’. For example, imagine an Overview that includes two systematic reviews. Systematic review 1 includes studies comparing intervention A with intervention B, and finds that A is more effective than B. Systematic review 2 includes studies comparing intervention B with intervention C, and finds that B is more effective than C. It would be tempting for the Overview authors to conclude that A was more effective than C. However, this would require an indirect comparison, a statistical procedure that compares two interventions (i.e. A vs. C) via a common comparator (i.e. B) despite the fact that the two interventions have never been compared directly against each other within a primary study (Glenny et al 2005).

We discourage indirect comparisons in Overviews. This is especially relevant for authors conducting Overviews that examine multiple interventions for the same condition or population; it is also relevant for authors regardless of whether the systematic reviews included in the Overview present their data using meta-analysis or simple narrative summaries of results. The reason is that the assumption underlying indirect comparison – the transitivity assumption – can rarely be assessed using only the information provided in the systematic reviews (see Section V.3.2).

Overviews that examine multiple interventions for the same condition or population will often juxtapose data from different systematic reviews. Sometimes, these data appear in the same table or figure. Overviews that present data in this way can inadvertently encourage readers to make their own indirect comparisons. In cases where Overviews may facilitate inappropriate informal indirect comparisons, Overview authors must avoid ‘comparing’ across systematic reviews. This can be achieved in the following ways:

- Use properly worded research question(s) and objectives (e.g. ‘Which interventions are effective in treating disorder X?’ as opposed to ‘Which intervention works best for treating disorder X?’).

- Interpret results and conclusions appropriately (e.g. ‘Compared to placebo, interventions A and D seem to be effective in treating disorder X, while interventions B and C do not seem to be effective’).

- Provide a clear explanation of the dangers associated with informal indirect comparisons to readers (e.g. ‘It may be tempting to conclude that intervention A is more effective than intervention C since the effect estimate for A versus placebo was twice as large as that for C versus placebo; however, the studies assessing both interventions differed in a number of ways, and we strongly urge readers against making this type of inappropriate informal indirect comparison’). Similar caveats can also be provided in data tables and figures.

V.4.2 Defining the research question(s)

Overview authors should begin by clearly defining the scope of the Overview. Overviews are typically broader in scope than reviews of interventions, but their research question(s) should still be specific, focused, and well-defined. An Overview’s research question should include a clear description of the populations, interventions, comparators, outcome measures, time periods, and settings. For Overviews that examine different interventions for the same condition or population, the primary objective of the Overview may be stated in the following form: ‘To summarize systematic reviews that assess the effects of [interventions or comparisons] for [health problem] for/in [types of people, disease or problem, and setting]’.

Because Overviews are typically broad in scope, it may be necessary to restrict the research question(s) if there is substantial variation in the questions posed by the different systematic reviews. For example, authors may wish to restrict to a single disorder (instead of multiple disorders) or to specific participant characteristics (such as a specific age group, disease severity, setting, or type of co-morbidity). When deciding whether and how to restrict the scope, authors must keep in mind the perspective of the decision maker to ensure that the research question(s) remain clinically appropriate and useful. There should be adequate justification for any restrictions.

Overviews are constrained by the eligibility criteria of their included systematic reviews. It is therefore possible that Overview authors will need to modify or refine their research question(s) (and perhaps also their methodology) as their knowledge of the underlying systematic reviews evolves. Authors should avoid introducing bias when making post-hoc modifications, and all modifications should be documented with a rationale (see Chapter 1).

V.4.3 Developing criteria for including systematic reviews

The research question(s) specified in Section V.4.2 should be used to directly inform the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria should include a clear description of all relevant characteristics (i.e. populations, interventions, comparators, outcome measures, time periods, settings) as well as information about the study design that will be included (i.e. systematic reviews). Chapter 3 provides useful advice about developing criteria for including studies. Though it is written for authors of reviews of interventions, much of the guidance is relevant to Overview authors as well.

The following three considerations also apply when including systematic reviews:

First, Overview authors must clearly specify the criteria they will use to determine whether publications are considered ‘systematic reviews’. Chapter 1, Section 1.1 provides a definition of a systematic review; however, Overview authors will need to add specific criteria to the definition to guide inclusion decisions (e.g. define “explicit, reproducible methodology”, comprehensive search, acceptable methods for assessing validity of included studies, etc). While Cochrane Reviews of interventions will adhere to the Cochrane definition of a systematic review; non-Cochrane publications show variation in the use of the term ‘systematic review’. Not every non-Cochrane publication that is labelled as a ‘systematic review’ will meet a given definition of a systematic review, while some publications that are not labelled as ‘systematic reviews’ might meet a given definition of a systematic review. Therefore, a focus on pre-established criteria should take priority when making decisions around inclusion.

Second, Overview authors must consider whether to include systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials only, or systematic reviews that include variable study designs such as observational studies. Current guidance does not recommend combining data from randomized trials and observational studies (Shea et al 2017); therefore, if Overview authors are to analyse data from different study designs separately, then they will only be able to do this if the data from systematic reviews are also presented (or available) separately.

Third, Overview authors are likely to encounter groups of two or more systematic reviews that examine the same intervention for the same disorder and that include some of the same primary studies. Authors must consider in advance whether and how to include these ‘overlapping reviews’ in the Overview. This consideration is described in detail in Section V.4.4, as it has methodological implications for all subsequent stages of the Overview process.

V.4.4 Managing overlapping systematic reviews

As the number of published systematic reviews increases (Page et al 2016), it is becoming common for Overview authors to identify two or more relevant systematic reviews that address the same (or very similar) research questions, and that include many (but not all) of the same underlying primary studies. There are two main challenges associated with including these overlapping reviews in Overviews (Thomson et al 2010, Smith et al 2011, Cooper and Koenka 2012, Baker et al 2014, Conn and Coon Sells 2014, Pieper et al 2014, Caird et al 2015, Biondi-Zoccai 2016, Pollock et al 2016, Ballard and Montgomery 2017, Pollock et al 2017a, Pollock et al 2019b):

First, including overlapping reviews may introduce bias by including the same primary study’s outcome data in an Overview multiple times because the study was included in multiple systematic reviews. If the Overview authors intend to summarize outcome data (see Section V.4.13), double-counting outcome data will give data from some primary studies too much influence. If the Overview authors intend to re-analyse outcome data (see Section V.4.13), double-counting outcome data gives data from some primary studies too much statistical weight and produces overly precise estimates of intervention effect.

Second, Overviews that contain overlapping reviews are complex. All stages of the Overview process will necessarily become more time- and resource-intensive as Overview authors determine how to search for, identify, include, assess the quality of, extract data from, and analyse and report the results of overlapping reviews in a systematic and transparent way. This is especially true when the overlapping reviews are of variable conduct, quality, and reporting, or when they have discordant results and/or conclusions.

To date, Overview authors have used several approaches, described below, to manage overlapping reviews. The most appropriate approach may depend on the purpose of the Overview and on the method of data analysis (see Section V.4.12). For example, if the purpose is to answer a new review question about a subpopulation of the participants included in the existing systematic reviews, authors may wish to re-extract and re-analyse outcome data from a set of non-overlapping reviews. However, if the purpose is to present and describe the current body of systematic review evidence on a topic, it may be appropriate to include the results of all relevant systematic reviews, regardless of topic overlap.

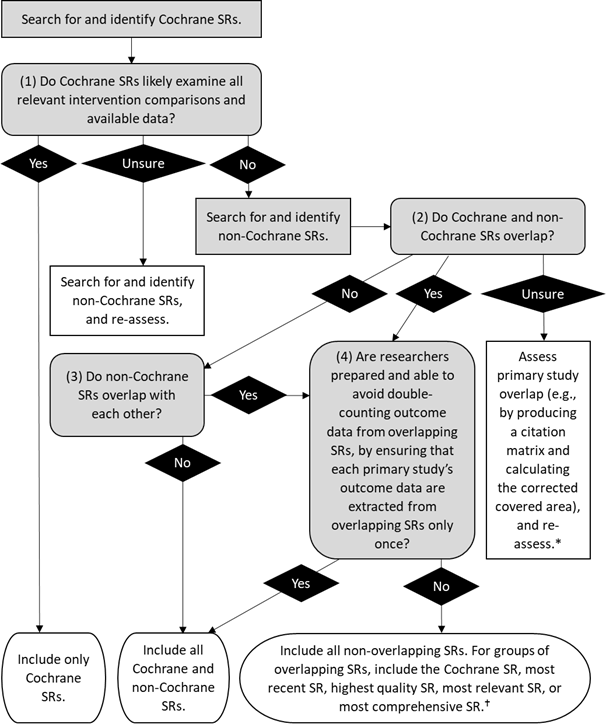

Figure V.4.a contains an evidence-based decision tool to help authors determine whether and how to include overlapping reviews in an Overview (modified from Pollock et al (2019b)). The main decision points, inclusion decisions, and considerations are summarized below. See Pollock et al (2019b) and Pollock et al (2019a) for full details. Note that the decision tool is based on the assumption that Overview authors are motivated to avoid double-counting primary study outcome data.

Decision point 1: Do Cochrane reviews of interventions likely examine all relevant intervention comparisons and available data? If the relevant Cochrane reviews of interventions are deemed comprehensive, it may be possible to avoid the issue of overlapping reviews altogether by including only Cochrane Reviews of interventions. This is because Cochrane attempts to avoid duplication of effort by publishing only one review of interventions on any given topic, whereas multiple non-Cochrane systematic reviews may exist. This may be desirable as Cochrane Reviews of interventions are more likely to: be up-to-date (Shojania 2007); be of higher methodological quality (Pollock et al 2017b); assess and report the risk of bias of their included primary studies (Hopewell et al 2013); assess and report the certainty of evidence for important outcomes (Akl et al 2015); and have more standardized conduct and reporting (Peters et al 2015). However, Cochrane Reviews of interventions are also fewer in number than non-Cochrane systematic reviews, and they often include less diverse study designs and fewer primary studies and interventions (Page et al 2016). As such, they may not provide comprehensive coverage of the topic area in question (Page et al 2016). If Overview authors are unsure whether the Cochrane reviews of interventions are comprehensive, they may opt to search for and identify Cochrane and/or non-Cochrane systematic reviews (see Sections V.4.5and V.4.6 for guidance) and reassess.

Decision points 2 and 3: Do the included Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews overlap? If Overview authors suspect that the Cochrane Reviews of interventions are not comprehensive, an appropriate next step is to search for and identify non-Cochrane systematic reviews and assess whether the included systematic reviews contain overlapping primary studies. If there is no overlap, authors can include all relevant Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews without concern for double-counting primary study outcome data. However, this situation is likely to be rare (Pollock et al 2019a). If Overview authors are unsure whether or how much overlap exists between the Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews, they may opt to assess primary study overlap (see Section V.4.7 for guidance) and reassess.

Decision point 4: Are authors prepared and able to avoid double-counting outcome data from overlapping reviews, by ensuring that each primary study’s outcome data are extracted from overlapping reviews only once? If there is overlap between the relevant systematic reviews, authors can include all relevant Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews and take care to avoid double-counting outcome data from overlapping primary studies. This is the only way to ensure that all outcome data from all relevant systematic reviews are included in the Overview. However, as described above, this inclusion decision is time-intensive and methodologically complex. Alternatively, authors who are not prepared or able to avoid double-counting outcome data from overlapping reviews, but who still wish to include non-Cochrane systematic reviews in the Overview, may choose to avoid including overlapping reviews by using pre-defined criteria to prioritize specific systematic reviews for inclusion when faced with multiple overlapping reviews. Authors can achieve this by including all non-overlapping reviews, and selecting the Cochrane, most recent, highest quality, “most relevant”, or “most comprehensive” systematic review for groups of overlapping reviews. This inclusion decision may represent a trade-off between the above-mentioned inclusion decisions by maximizing the amount of outcome data included in the Overview while also avoiding potential challenges related to overlapping reviews.

As previously mentioned, authors who are unable to avoid double-counting outcome data for methodological or logistical reasons may still opt to include all relevant Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews in the Overview. In these cases, authors should provide methodological justification, assess and document the extent of the primary study overlap (see Section V.4.7), and discuss the potential limitations of this approach.

In summary, the potential inclusion decisions are to:

- include only Cochrane reviews of interventions (to avoid double-counting outcome data);

- include all Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews (and avoid double-counting outcome data);

- include all Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews (regardless of double-counting outcome data);

- include all non-overlapping systematic reviews, and for groups of overlapping reviews include the Cochrane, most recent, highest quality, “most relevant”, or “most comprehensive” systematic review (to avoid double-counting outcome data).

Authors wishing to exclude poorly conducted systematic reviews from an Overview may also opt to use results of quality/risk of bias assessments as an exclusion criterion before applying one of the above sets of inclusion criteria (Pollock et al 2017b). Guidance for assessing the methodological quality/risk of bias of systematic reviews can be found in Section V.4.9.

Figure V.4.a Decision tool to help researchers make inclusion decisions in Overviews. Modified from Pollock et al (2019b) licensed under CC BY 4.0.

* See Section V.4.7 for guidance on assessing primary study overlap. † Researchers should operationalize the criteria used to define “most recent”, “highest quality”, “most relevant” or “most comprehensive”.

V.4.5 Searching for systematic reviews

Once Overview authors have developed a protocol, including defining the research question, developing criteria for including systematic reviews, and considering how they will address issues related to overlapping systematic reviews, the next step is to conduct a literature search that is comprehensive and reproducible. Note that authors may have already conducted the literature search if they wished to use this information to help inform their decision about how to address overlapping reviews in their Overview (see ‘Decision point 1’ of the decision tool presented in Section V.4.4). Though written for authors of reviews of interventions, much of the guidance on conducting literature searches provided in Chapter 4 is relevant to Overview authors as well. Notable differences are discussed below.

Overviews that only include Cochrane Reviews of interventions will only need to search the CDSR. If non-Cochrane systematic reviews will be included in the Overview, additional databases and systematic review repositories will need to be searched (Aromataris et al 2015, Caird et al 2015, Biondi-Zoccai 2016, Pollock et al 2016, Pollock et al 2017a). In general, MEDLINE/PubMed and Embase index most systematic reviews (Hartling et al 2016). Authors may also search additional regional and subject-specific databases (e.g. LILACS, CINAHL, PsycINFO) and systematic review repositories such as Epistemonikos and KSR Evidence.

Many databases that contain non-Cochrane systematic reviews index a wide variety of study designs, including, but not limited to, systematic reviews. Authors should therefore attempt as much as possible to restrict their searches to capture systematic reviews while simultaneously minimizing the capture of non-systematic review publications (Smith et al 2011, Cooper and Koenka 2012, Aromataris et al 2015, Biondi-Zoccai 2016, Pollock et al 2016, Pollock et al 2017a). Authors can do this by using search terms and MeSH headings specific to the systematic review study design (e.g. ‘systematic review’, ‘meta-analysis’) and by using validated systematic review search filters. A list of validated search filters is available here.

V.4.6 Selecting systematic reviews for inclusion

V.4.6.1 Identifying systematic reviews that meet the inclusion criteria

Each document retrieved by the literature search must be assessed to see whether it meets the eligibility criteria of the Overview. Note that authors may have already selected systematic reviews for inclusion if they wished to use this information to help inform their decision about how to address overlapping reviews in their Overview (see ‘Decision point 1’ of the decision tool presented in Section V.4.4). Chapter 4, Section 4.6 describes the key steps involved in the inclusion process. Though it is written for authors of reviews of interventions, much of the guidance is relevant to Overview authors as well. Notable differences are discussed below.

There are two considerations related to assessing Cochrane Reviews of interventions for inclusion in Overviews. First, the search of the CDSR may retrieve Protocols. Second, there may be times when a review of interventions is not sufficiently up-to-date. In both of these cases, Overview authors should contact Cochrane Community Support (support@cochrane.org) and/or author team(s) to ask whether the relevant reviews of interventions are close to completion or in the process of being updated. If so, it may be possible to obtain pre-publication versions of the new or updated reviews of interventions, which can then be assessed for inclusion in the Overview. Authors should include any outstanding Protocols in the reference list of the Overview under the heading ‘Characteristics of reviews awaiting assessment’ (see Section V.5). When assessing non-Cochrane systematic reviews for inclusion, Overview authors must adhere to their pre-specified definition of a ‘systematic review’ (see Section V.4.3).

In cases where the Overview’s scope is narrower than the scope of one or more of the relevant systematic reviews, it is possible that only a subset of primary studies contained within the systematic reviews will meet the Overview’s eligibility criteria. Thus, the primary studies, as reported within the included systematic reviews, should be assessed for inclusion against the Overview’s inclusion criteria. Only the subset of primary studies that fulfil the Overview’s inclusion criteria should be included in the Overview. For example, Cates et al (2012) conducted an Overview examining safety of regular formoterol or salmeterol in children, but many relevant systematic reviews contained primary studies that were conducted in adults. Therefore, within the included systematic reviews, the authors only included those primary studies conducted in children.

V.4.6.2 Conducting supplemental searches for primary studies

Occasionally, after identifying all systematic reviews that meet the inclusion criteria, important gaps in coverage will remain (e.g. an important intervention may not be examined in any included systematic review, or a systematic review on an important intervention may be out-of-date). In rare cases, authors may consider conducting a supplemental search for primary studies that can overcome the deficiency in the included systematic reviews. However, authors considering this option should re-consider the appropriateness of the Overview format due to the additional complexities involved when working with both systematic reviews and primary studies within the same Overview. As stated in Section V.3.1, Overviews should not conduct study level searches or new systematic reviews within an Overview, so doing this would be at variance with standard methodological expectations of this review format. Additionally, there is no existing guidance on how to incorporate additional primary studies into Overviews appropriately.

V.4.7 Assessing primary study overlap within the included systematic reviews

An important step once authors have their final list of included systematic reviews is to map out which primary studies are included in which systematic reviews. Note that authors may have already assessed primary overlap within the included systematic reviews if they wished to use this information to help inform their decision about how to address overlapping systematic reviews in their Overview (see ‘Decision point 2’ of the decision tool presented in Section V.4.4).

At a minimum, authors may find it useful to create a citation matrix similar to Table V.4.b to visually demonstrate the amount of overlap. Authors should also narratively describe the number and size of the overlapping primary studies, and the amount of weight they contribute to the analyses. Authors may also wish to calculate the ‘corrected covered area’, which provides a numerical measure of the extent of primary study overlap between the systematic reviews. Pieper et al (2014) provides detailed instructions for creating citation matrices, describing overlap, and calculating the corrected covered area. If the included systematic reviews contain multiple intervention comparisons, Overview authors may wish to assess the amount of primary study overlap separately for each comparison. Information on the extent and nature of the primary study overlap should be clearly reported in the published Overview, especially for Overviews that are unable to avoid double-counting primary study data for methodological or logistical reasons.

When mapping the extent of overlap, note that the overlapping primary studies may be easily identifiable across systematic reviews because the references are the same. However, overlapping primary studies may not be easily identifiable across systematic reviews if different references are cited in different systematic reviews to describe different aspects of the same primary study (e.g. different subgroups, comparisons, outcomes, and/or time points).

Table V.4.b Template for a table mapping the primary studies contained within included systematic reviews*

|

|

Review 1 |

Review 2 |

Review 3 |

[...] |

Review ‘X’ |

|

Primary study 1 |

|||||

|

Primary study 2 |

|||||

|

Primary study 3 |

|||||

|

[...] |

|||||

|

Primary study ‘X’ |

* Place an ‘X’, ‘Yes’, ‘Included’, or similar note in relevant cells to indicate which systematic reviews include which primary studies.

V.4.8 Collecting, analysing, and presenting data from included systematic reviews: An introduction

Several types of data must be extracted from the systematic reviews included in an Overview, including: data to inform risk of bias assessment of systematic reviews (and their included primary studies); descriptive characteristics of systematic reviews (and their included primary studies); quantitative outcome data; and certainty of evidence for important outcomes (Pollock et al 2016, Ballard and Montgomery 2017). It is highly desirable that methodological quality/risk of bias assessments and data extraction be conducted independently by two reviewers, with a process in place for resolving discrepancies, using piloted forms (see Chapter 5, Section 5.6).

Overview authors, especially those including non-Cochrane systematic reviews, should consider in advance how they will proceed if data they are interested in extracting are missing from, inadequately reported in, or reported differently across, systematic reviews (Pollock et al 2016, Ballard and Montgomery 2017). Authors might simply note the gap in coverage in their Overview and state that certain data were not available in the systematic reviews. Alternatively, they might choose to extract the missing data directly from the underlying primary studies. Referring back to underlying primary studies can enhance the comprehensiveness and rigour of the Overview, but will also require additional time and resources. If authors find they are extracting a large amount of data from primary studies, they should re-consider the appropriateness of the Overview format and may consider conducting a systematic review instead.

The next sections contain methodological guidance for collecting, analysing, and presenting data from included systematic reviews.

V.4.9 Assessing methodological quality/risk of bias of included systematic reviews

Overview authors can use one of three tools to assess the methodological quality or risk of bias of systematic reviews included in Overviews. Methodological quality refers to critical appraisal of a systematic review and the extent to which authors conducted and reported their research to the highest possible standard. Bias refers to systematic deviation of results or inferences from the truth. These deviations can occur as a result of flaws in design, conduct, analysis, and/or reporting. It is not always possible to know whether an estimate is biased even if there is a flaw in the study; further, it is difficult to quantify and at times to predict the direction of bias. For these reasons, reviewers refer to ‘risk of bias’ (Chapter 7, Section 7.2). Note that authors may have already assessed methodological quality/risk of bias of included systematic reviews if they wished to use this information to help inform their decision about how to address overlapping systematic reviews in their Overview (see ‘Decision point 4’ of the decision tool presented in Section V.4.4).

The AMSTAR tool (Shea et al 2007) was designed to assess methodological quality of systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials, and to date has been the most commonly used tool in Overviews (Hartling et al 2012, Pieper et al 2012, Pollock et al 2016). It was intended to be “a practical critical appraisal tool for use by health professionals and policy makers who do not necessarily have advanced training in epidemiology, to enable them to carry out rapid and reproducible assessments of the quality of conduct of systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials of interventions” (Shea et al 2007). Researchers wishing to use this tool can refer to Pollock et al (2017b) for empirical evidence and recommendations on using AMSTAR in Overviews.

The AMSTAR 2 tool (Shea et al 2017) is an updated version of the original AMSTAR tool. It can be used to assess methodological quality of systematic reviews that include both randomized and non-randomized studies of healthcare interventions. AMSTAR2 should assist in identifying high quality systematic reviews (Shea et al 2017) and includes the following critical domains: protocol registered before start of review; adequacy of literature search; justification for excluded studies; risk of bias for included studies; appropriateness of meta-analytic methods; consideration of risk of bias when interpreting results; and assessing presence and likely impact of publication bias (Shea et al 2017). The tool provides guidance to rate the overall confidence in the results of a review (high, moderate, low or critically low depending on the number of critical flaws and/or non-critical weaknesses). Detailed guidance on using the AMSTAR2 tool is available here. Given that this is an updated version of AMSTAR with the intent to improve upon AMSTAR and clarify some points, this tool may be preferred for use in future Overviews.

Lastly, the recently developed ROBIS tool (Whiting et al 2016) can be used by authors wishing to assess risk of bias of systematic reviews in Overviews. ROBIS was designed to be used for systematic reviews within healthcare settings that address questions related to interventions, diagnosis, prognosis and aetiology (Whiting et al 2016). The tool involves three phases: 1) assessing relevance (which is considered optional but may be used to assist with selecting systematic reviews for inclusion; see Section V.4.6); 2) identifying concerns with the systematic review process; and 3) judging overall risk of bias for the systematic review (low, high, unclear). The second phase includes four domains which may be sources of bias in the systematic review process: study eligibility criteria, identification and selection of studies, data collection and study appraisal, and synthesis and findings. The tool is available on the ROBIS website. This website also contains pre-formatted data extraction forms and data presentation tables.

We cannot currently recommend one tool over another due to a lack of empirical evidence on this topic. However, regardless of which tool is used, Overview authors should include: a table that provides a breakdown of how each systematic review was rated on each question of the tool, the rationale behind the assessments, and an overall rating for each systematic review (if appropriate). Authors can then use the results of the quality/risk of bias assessments to help contextualize the Overview’s evidence base (e.g. by assessing whether and to what extent SR methods may have affected the Overview’s comprehensiveness and results).

V.4.10 Collecting and presenting data on risk of bias of primary studies contained within included systematic reviews

When conducting an Overview, authors should extract and report the domain-specific and/or overall quality/risk of bias assessments for the relevant primary studies contained within each included systematic review. Chapter 7 and Chapter 8 provide a comprehensive discussion of approaches to assessing risk of bias, the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool, risk of bias domains, and how to summarize and present risk of bias assessments in a review of interventions. The key risk of bias domains cover bias arising from the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in measurement of the outcome, and bias in selection of the reported result. Other chapters in the Handbook provide information on risk of bias assessments and critical appraisal of evidence from other study designs (e.g. non-randomized studies) and type of data (e.g. qualitative research).

Ideally, authors should extract the assessments that are presented in each included systematic review (i.e. they should not repeat or update the risk of bias assessments that have already been conducted by systematic review authors). They can then present the assessments in narrative and/or tabular summaries (Bialy et al 2011, Foisy et al 2011a). However, it is possible that different systematic reviews, especially non-Cochrane systematic reviews, may have used different tools, or different parts of tools, to assess methodological quality/risk of bias. In these situations, authors should extract the disparate quality/risk of bias assessments to the best of their ability, despite the variability across systematic reviews. Authors then have two options (Cooper and Koenka 2012, Conn and Coon Sells 2014, Caird et al 2015, Biondi-Zoccai 2016, Pollock et al 2016, Ballard and Montgomery 2017). They can provide narrative and/or tabular summaries of the assessments (Bialy et al 2011, Foisy et al 2011a). Or, they can supplement the existing assessments by referring to the original primary studies and extracting data pertaining to the missing quality/risk of bias domains (Foisy et al 2011b, Pollock et al 2017c).

V.4.11 Collecting and presenting data on descriptive characteristics of included systematic reviews (and their primary studies)

Overview authors must extract information about the descriptive characteristics of each systematic review included in the Overview. As a starting point, for each systematic review, it may be useful to extract the information listed in Box V.4.a (Thomson et al 2010, Smith et al 2011, Conn and Coon Sells 2014, Aromataris et al 2015, Biondi-Zoccai 2016, Pollock et al 2016, Pollock et al 2017a). This information can then be reported in a ‘Characteristics of included reviews’ table (Foisy et al 2011a, Jones 2012). Additional descriptive data may need to be extracted, depending upon the specific requirements or objectives of the Overview. Authors should also note in the text any discrepancies between the outcomes included in the systematic reviews and those pre-specified in the Overview.

Box V.4.a Descriptive characteristics of systematic reviews (and their primary studies) that Overview authors may wish to extract from included systematic reviews

|

V.4.12 Collecting, analysing, and presenting quantitative outcome data

There are two main ways to analyse outcome data in an Overview modified from Pollock et al (2016) and Ballard and Montgomery (2017). Summarizing outcome data involves presenting data in the Overview exactly as they are presented in the included systematic reviews; this applies to both narratively reported study-level data, as well as meta-analysed data. Re-analysing outcome data involves extracting outcome data from the included systematic reviews, analysing the data in a way that differs from the analyses conducted in the systematic reviews, and presenting the re-analysed data in the Overview. The most appropriate method of data analysis will likely depend upon the purpose of the Overview, the specific topic area, and the characteristics of the included systematic reviews. For example, if the purpose is to answer a new review question about a subpopulation of the participants included in the existing systematic reviews, authors may wish to extract outcome data for only those participants of interest and re-analyse the data. However, if the purpose is to present and describe the current body of systematic review evidence on a topic, it may be appropriate to include the results of all relevant systematic reviews as they were presented in the underlying systematic reviews. Both methods of data analysis can be used regardless of whether the Overview includes Cochrane and/or non-Cochrane systematic reviews; however, authors may find that they encounter more issues when re-analysing outcome data from non-Cochrane systematic reviews. Both methods are discussed below. For clarity, the methods are presented as distinct approaches to analysing outcome data, though in reality these two approaches lie on a continuum.

V.4.12.1 Summarizing outcome data

Summarizing outcome data provides readers with a map of the available evidence by presenting individual narrative summaries of the data contained within each included systematic review (including effect estimates and 95% confidence intervals). The purpose is to describe and summarize a group of related systematic reviews (and their outcome data) so that readers are presented with the content and results of the systematic reviews. The purpose may also be to identify and describe the interventions, comparators, outcomes and/or results among related systematic reviews.

When summarizing outcome data, data should be extracted as they were reported in the underlying systematic reviews and then reformatted and presented in text, tables and/or figures, as appropriate. The effect estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and measures of heterogeneity (if studies are pooled) should all be extracted. Overview authors should rely on the analyses reported in the included systematic reviews as much as possible. There should be limited re-analysis or re-synthesis of outcome data (see Section V.4.12.2).

Examples of Overviews that summarized outcome data are Farquhar et al (2015) and Welsh et al (2015).

V.4.12.2 Re-analysing outcome data

Re-analysing outcome data involves extracting relevant outcome data from included systematic reviews and re-analysing this data (e.g. using meta-analysis) in a way that differs from the original analyses conducted in the systematic reviews. Overview authors may choose to re-analyse outcome data for several reasons. First, if the objective of the Overview is to answer a different clinical question, authors may select and re-analyse only the data specific to that question (e.g. effect of interventions in children, but not adults). Second, if most, but not all, of the systematic reviews have analysed specific populations or subgroups, Overview authors may apply these analyses to the remainder of the systematic reviews so that consistent information are reported across the systematic review topics. Third, Overview authors may choose to re-analyse data if different summary measures or models were used across the included systematic reviews, as this can allow authors to present results in a consistent fashion across the systematic review topics (e.g. present all estimates as relative or absolute). Lastly, Overview authors may choose to analyse data where they were not previously meta-analysed in a systematic review. Care should be taken in these last two instances, as systematic review authors have likely selected their approach to analysis based on approved methods and in-depth knowledge of individual studies. Overview authors should understand the reasons behind the systematic review authors’ choice of analytic methods when determining whether their desired methods of re-analysing outcome data are appropriate.

Overview authors who re-analyse outcome data should use the standard meta-analytic principles described in Chapter 10. Note that authors wishing to re-analyse outcome data may only be able to do so if the clinical parameters and statistical aspects of the included systematic reviews are sufficiently reported. When conducting this type of analysis, authors should try as much as possible to present re-analysed outcomes in a standardized way (e.g. using fixed or random effects modelling and using a consistent measure of effect for each outcome). Overview authors must also guard against making inappropriate informal indirect comparisons about the comparative effectiveness of two or more interventions (see Section V.4.1). Authors with access to the CDSR can download Review Manager files for included Cochrane Reviews of interventions to help expedite data extraction.

Examples of Overviews that re-analysed outcome data are Bialy et al (2011), Cates et al (2012), Cates et al (2014), Pollock et al (2017c).

More detail on re-analysing outcome data can be found in Thomson et al (2010), Cooper and Koenka (2012), Pollock et al (2016), Ballard and Montgomery (2017), Pollock et al (2017a).

V.4.12.3 Presenting outcome data

Overview authors can present their summarized or re-analysed outcome data narratively and in results tables. There is no specific format for the tables, but authors should follow the principles for displaying outcome data outlined in Chapter 14. Overview authors could:

- Present narrative summaries, with or without corresponding tables, of the outcome data contained within the systematic reviews. For example, Overview authors could present each outcome measure in turn across systematic reviews (Brown and Farquhar 2014, Farquhar et al 2015, Welsh et al 2015), or they could present the results from each systematic review in turn (Jones 2012, Hindocha et al 2015). Overview authors could also present groups of similar systematic reviews and/or outcome measures together (Bialy et al 2011, Foisy et al 2011a, Payne et al 2012, Pollock et al 2017c); this may allow authors to group similar populations, interventions, or outcome measures together, while still presenting outcome data sequentially.

- Organize results into categories (e.g. ‘clinically important’ or ‘not clinically important’; or ‘effective interventions’, ‘promising interventions’, ‘ineffective interventions’, ‘probably ineffective interventions’ and ‘no conclusions possible’), avoiding the categorization of results into statistically significant vs not significant categories, and use these data to provide a map of the available evidence (Flodgren et al 2011, Worswick et al 2013, Farquhar et al 2015).

- Present a new conceptual framework, or modify an existing framework. For example, authors could present a grid of interventions versus outcomes; they could then indicate how many primary studies and subjects contribute outcome data, and the direction of effect for each outcome (Flodgren et al 2011). Authors could also map their included systematic reviews to specific taxonomies of interventions and describe the effectiveness of each category of interventions (Ryan et al 2014). Any frameworks used to present outcome data should be specified a priori at the protocol stage, or indicated as post hoc in the report.

Additional suggestions for presenting outcome data, with examples, are provided in Ryan et al (2009), Smith et al (2011), Thomson et al (2013), Biondi-Zoccai (2016), Pollock et al (2017a).

Table V.4.c contains a template for a ‘Summary of findings’ table that authors may wish to use. The table layout and terminology are explained in Chapter 14, and assessing certainty of evidence using the GRADE tool is explained in Section V.4.13. When creating these tables, authors should also include references where appropriate to indicate which outcome data come from which systematic reviews. When creating ‘Summary of findings’ tables, we caution Overview authors against selectively reporting only statistically significant outcomes. Also note that Overview authors who choose to juxtapose data from different systematic reviews in a single table or figure may be inviting readers to make their own informal indirect comparisons; tables of this sort should only be used if Overview authors: avoid ‘comparing’ across systematic reviews, appropriately interpret results, and describe the caveats to readers (see Section V.4.1).

Table V.4.c Template for a ‘Summary of findings’ table

|

Interventions for [Condition] in [Population] |

|||||||

|

Outcome |

Intervention and Comparator |

Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) |

Relative effect (95% CI) |

Number of participants (studies) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

Comments |

|

|

Assumed risk |

Corresponding risk |

||||||

|

With comparator |

With intervention |

||||||

|

Outcome #1 |

|||||||

|

Intervention and comparator 1 |

|||||||

|

Intervention and comparator 2 |

|||||||

|

[…] |

|||||||

|

Intervention and comparator ‘X’ |

|||||||

|

Outcome #2 |

|||||||

|

Intervention and comparator 1 |

|||||||

|

Intervention and comparator 2 |

|||||||

|

[…] |

|||||||

|

Intervention and comparator ‘X’ |

|||||||

|

Outcome ‘X’ |

|||||||

|

Intervention and comparator 1 |

|||||||

|

Intervention and comparator 2 |

|||||||

|

[…] |

|||||||

|

Intervention and comparator ‘X’ |

|||||||

V.4.13 Assessing certainty of evidence of quantitative outcome data using the GRADE tool

Similar to Cochrane reviews of interventions, Cochrane Overviews should use the GRADE tool (Guyatt et al 2008) to assess and report the certainty of evidence (i.e. the confidence we have in the effect estimate) for each pre-defined, clinically important outcome of interest in the Overview. If possible, Overview authors should extract and report the GRADE assessments presented in the included systematic reviews. However, there may be caveats involved, especially when non-Cochrane systematic reviews are included in Overviews. For example, some systematic reviews may not contain GRADE assessments, may contain limited GRADE assessments, may present aggregated (instead of individual) assessments, or may use tools other than GRADE to assess certainty of evidence. Further, if Overviews re-extract and re-analyse outcome data from systematic reviews, the GRADE assessments in the systematic reviews may no longer be relevant. In these cases, Overview authors must determine whether they will need to conduct GRADE assessments themselves using the information reported in the systematic reviews (Biondi-Zoccai 2016, Pollock et al 2016). See Meader et al (2014) for tips on assessing GRADE in systematic reviews.

V.5 Format and reporting guidelines for Cochrane Overviews of Reviews

As the format and reporting guidelines for Cochrane Overviews (and protocols) are similar to those for Cochrane reviews of interventions (and protocols), Overview authors can refer to Chapter III for general guidance on reporting. However, authors should remain mindful that Cochrane Overviews will have certain unique reporting requirements. For example: titles should contain the phrase ‘an Overview of Reviews’; titles should state whether Cochrane reviews of interventions and/or non-Cochrane systematic reviews are included; relevant section headings should refer to ‘reviews’ instead of ‘studies’; and there should be separate subheadings discussing the methodological quality of included systematic reviews and that of their underlying primary studies. The sections of a Cochrane Overview and protocol are listed in Box V.5.a and Box V.5.b.

Further, Overviews will have unique limitations that should be mentioned in the Discussion. As with Cochrane Reviews of interventions, authors should comment on factors that might be within or outside of the control of the Overview authors, including whether all relevant systematic reviews were identified and included in the Overview, any gaps in coverage of existing reviews (and potential priority areas for systematic reviews), whether all relevant data could be obtained (and implications for missing data), and whether the methods used (for example, searching, study selection, data collection and analysis at both the systematic review (see Chapter 4, Section 4.5) and overview levels) could have introduced bias.

Box V.5.a Sections of a protocol for a Cochrane Overview of Reviews

|

Title Protocol information: Authors Contact person Dates The protocol: Background Objectives Methods: Criteria for selecting reviews for inclusion:* Types of reviews* Types of participants Types of interventions Types of outcome measures Search methods for identification of reviews* Data collection and analysis Quality of included reviews* Risk of bias of primary studies included in reviews* Quality of evidence in included reviews* Additional information: Acknowledgements Contributions of authors Declarations of interest Sources of support Registration and protocol Data, code and other materials What’s new History Published notes References: Supplementary information: Search strategies Other supplementary materials |

* Note that these headers refer to ‘systematic reviews’ instead of ‘primary studies’.

Box V.5.b Sections of a Cochrane Overview of Reviews

|

Title Review information: Authors Contact person Dates Abstract: Background Objectives Methods Main results Authors’ conclusions Funding Registration Plain language summary: Plain language title Summary text Summary of findings' tables The Overview: Background Objectives Methods: Criteria for selecting reviews for inclusion:* Types of reviews* Types of participants Types of interventions Types of outcome measures Search methods for identification of reviews* Data collection and analysis Quality of included reviews* Risk of bias of primary studies included in reviews* Quality of evidence in included reviews* Results: Description of included reviews* Methodological quality of included reviews:* Quality of included reviews* Risk of bias of primary studies included in reviews* Effects of interventions Discussion Summary of main results Overall completeness and applicability of evidence Quality of the evidence Potential biases in the overview process Agreements and disagreements with other studies and/or reviews Authors’ conclusions: Implication for practice Implication for research Additional information: Acknowledgements Contributions of authors Declarations of interest Sources of support Registration and protocol Data, code and other materials What’s new History Published notes References: Other published versions of this review Figures: Tables: Supplementary information: Search strategies Characteristics of included reviews Characteristics of excluded reviews Characteristics of reviews awaiting assessment Characteristics of ongoing reviews Data and Analyses Data package Other supplementary materials |

* Note that these headers refer to ‘systematic reviews’ instead of ‘primary studies’.

V.6 Updating a Cochrane Overview

Regular updating of Cochrane Overviews is very important and follows the same process as updating Cochrane Reviews of interventions (see Chapter IV). In many cases, only minor changes to the Cochrane Overview will be required. However, when new eligible systematic reviews are published, or when the results of any of the included Cochrane Reviews of interventions change, the Overview will require more extensive revisions.

V.7 Chapter information

Authors: Michelle Pollock, Ricardo M Fernandes, Lorne A Becker, Dawid Pieper, and Lisa Hartling.

Acknowledgements: This chapter builds on a previous version, which was authored by Lorne A Becker and Andy Oxman. Methods for Cochrane Overviews were originally developed by the Umbrella Reviews Methods Group (now called the Comparing Multiple Interventions Methods Group). We thank Tianjing Li, Andrew Booth, Miranda Cumpston, Gerald Gartlehner, Julian Higgins, and Penny Whiting for providing feedback on the current version of the chapter.

Funding: This work was supported in part by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, including an operating grant and new investigator salary award.

V.8 References

Akl E, Carrasco-Labra A, Brignardello-Petersen R, Neumann I, Johnston BC, Sun X, Briel M, Busse JW, Ebrahim S, Granados CE, Iorio A, Irfan A, Garcia LM, Mustafa RA, Ramirez-Morera A, Selva A, Sola I, Sanabria AJ, Tikkinen KAO, Vandvik PO, Vernooij RWM, Zazueta OE, Zhou Q, Guyatt GH, Alonso-Coello P. Reporting, handling and assessing the risk of bias associated with missing participant data in systematic reviews: a methodological survey. BMJ Open 2015; 5: 8.

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 2015; 13: 8.

Baker P, Costello J, Dobbins M, Waters E. The benefits and challenges of conducting an overview of systematic reviews in public health: a focus on physical activity. Journal of Public Health 2014; 36: 4.

Ballard M, Montgomery P. Risk of bias in overviews of reviews: a scoping review of methodological guidance and four-item checklist. Research Synthesis Methods 2017; 8: 16.

Bialy L, Foisy M, Smith M, Fernandes R. The Cochrane Library and the treatment of bronchiolitis in children: an overview of reviews. Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal 2011; 6: 17.

Biondi-Zoccai G. Umbrella Reviews: Evidence Synthesis with Overviews of Reviews and Meta-Epidemiologic Studies. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

Brown J, Farquhar C. Endometriosis: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014; 3: CD009590.

Caird J, Sutcliffe K, Kwan I, Dickson K, Thomas J. Mediating policy-relevant evidence at speed: are systematic reviews of systematic reviews a useful approach? Evidence and Policy 2015; 11: 16.

Cates C, Wieland L, Oleszczuk M, Kew K. Safety of regular formoterol or salmeterol in children with asthma: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012; 10: CD010005.

Cates C, Wieland L, Oleszczuk M, Kew K. Safety of regular formoterol or salmeterol in adults with asthma: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014; 2: CD010314.

Cochrane Editorial Unit. Cochrane Editorial and Publishing Policy Resource. 2015. Cochrane Editorial and Publishing Policy Resource

Conn VS, Coon Sells TG. WJNR welcomes umbrella reviews. Western Journal of Nursing Research 2014; 36: 147.

Cooper H, Koenka AC. The overview of reviews: unique challenges and opportunities when research syntheses are the principal elements of new integrative scholarship. American Psychologist 2012; 67: 16.

Derry C, Derry S, Moore R. Sumatriptan (all routes of administration) for acute migrains attacks in adults - overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014; 5: CD009108.

Farquhar C, Rishworth J, Brown J, Nelen W, Marjoribanks J. Assisted reproductive technology: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015; 7: CD010537.

Flodgren G, Eccles M, Shepperd S, Scott A, Parmelli E, Beyer F. An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011; 7: CD009255.

Foisy M, Boyle R, Chalmers J, Simpson E, Williams H. The prevention of eczema in infants and children: an overview of Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews. Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal 2011a; 6: 1322.

Foisy M, Ali S, Geist R, Weinstein M, Michail S, Thakkar K. The Cochrane Library and the treatment of chronic abdominal pain in children and adolescents: an overview of reviews. Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal 2011b; 6: 1027.

Glenny A, Altman D, Song F, Sakarovitch C, Deeks J, D'Amico R, Bradburn M, Eastwood A. Indirect comparisons of competing interventions. Health Technology Assessment 2005; 9: 134, iii-iv.

Guay J, Choi P, Suresh S, Albert N, Kopp S, Pace N. Neuraxial blockade for the prevention of postoperative mortality and major morbidity: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014; 1: CD010108.

Guyatt G, Oxman A, Vist G, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann H. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008; 336: 3.

Hartling L, Chisholm A, Thomson D, Dryden D. A descriptive analysis of overviews of reviews published between 2000 and 2011. Plos One 2012; 7: e49667.

Hartling L, Featherstone R, Nuspl M, Shave K, Dryden D, Vandermeer B. The contribution of databases to the results of systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2016; 16: 13.

Hindocha A, Beere L, Dias S, Watson A, Ahmad G. Adhesion prevention agents for gynaecological surgery: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015; 1: CD011254.

Hopewell S, Boutron I, Altman D, Ravaud P. Incorporation of assessments of risk of bias of primary studies in systematic reviews of randomised trials: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013; 3: 8.

Jones L. Pain management for women in labour: an overview of systematic reviews. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine 2012; 5: 2.

Meader N, King K, Llewellyn A, Norman G, Brown J, Rodgers M, Moe-Byrne T, Higgins J, Sowden A, Stewart G. A checklist designed to aid consistency and reproducibility of GRADE assessments: development and pilot validation. Systematic Reviews 2014; 3: 82.

Moore R, Derry S, Aldington D, Wiffen P. Adverse events associated with single dose oral analgesics for acute postoperative pain in adults-an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014; 10: CD011407.

Page M, Shamseer L, Altman D, Tetzlaff J, Sampson M, Tricco A, Catalá-López F, Li L, Reid E, Sarkis-Onofre R. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews of biomedical research: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Medicine 2016; 13: 30.

Payne C, Martin S, Wiffen P. Interventions for fatigue and weight loss in adults with advanced progressive illness. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012; 3: CD008427.

Peters J, Hooft L, Grolman W, Stegeman I. Reporting quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of otorhinolaryngologic articles based on the PRISMA Statement. Plos One 2015; 10: 11.

Pieper D, Buechter R, Jerinic P, Eikermann M. Overviews of reviews often have limited rigor: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2012; 65: 6.

Pieper D, Antoine S, Mathes T, Neugebauer E, Eikermann M. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2014; 67: 7.

Pollock A, Campbell P, Brunton G, Hunt H, Estcourt L. Selecting and implementing overview methods: implications from five exemplar overviews. Systematic Reviews 2017a; 6: 145.