James Thomas, Lisa M Askie, Jesse A Berlin, Julian H Elliott, Davina Ghersi, Mark Simmonds, Yemisi Takwoingi, Jayne F Tierney, Julian PT Higgins

Key Points:

- Cochrane Reviews should reflect the state of current knowledge, but maintaining their currency is a challenge due to resource limitations. It is difficult to know when a given review might become out of date, but tools are available to assist in identifying when a review might need updating.

- Living systematic reviews are systematic reviews that are continually updated, with new evidence being incorporated as soon as it becomes available. They are useful in rapidly evolving fields where research is published frequently. New technologies and better processes for data storage and reuse are being developed to facilitate the rapid identification and synthesis of new evidence.

- A prospective meta-analysis is a meta-analysis of studies (usually randomized trials) that were identified or even collectively planned to be eligible for the meta-analysis before the results of the studies became known. They are usually undertaken by a collaborative group including authors of the studies to be included, and they usually collect and analyse individual participant data.

- Formal sequential statistical methods are discouraged for standard updated meta-analyses in most circumstances for Cochrane Reviews. They should not be used for the main analyses, or to draw main conclusions. Sequential methods may, however, be used in the context of a prospectively planned series of randomized trials.

This chapter should be cited as: Thomas J, Askie LM, Berlin JA, Elliott JH, Ghersi D, Simmonds M, Takwoingi Y, Tierney JF, Higgins HPT. Chapter 22: Prospective approaches to accumulating evidence [last updated October 2019]. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5. Cochrane, 2024. Available from cochrane.org/handbook.

22.1 Introduction

Iain Chalmers’ vision of “a library of trial overviews which will be updated when new data become available” (Chalmers 1986), became the mission and founding purpose of Cochrane. Thousands of systematic reviews are now published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, presenting critical summaries of the evidence. However, maintaining the currency of these reviews through periodic updates, consistent with Chalmers’ vision, has been a challenge. Moreover, as the global community of researchers has begun to see research in a cumulative way, rather than in terms of individual studies, the idea of ‘prospective’ meta-analyses has emerged. A prospective meta-analysis (PMA) begins with the idea that future studies will be integrated within a systematic review and works backwards to plan a programme of trials with the explicit purpose of their future integration.

The first part of this chapter covers methods for keeping abreast of the accumulating evidence to help a review team understand when a systematic review might need updating (see Section 22.2). This includes the processes that can be put into place to monitor relevant publications, and algorithms that have been proposed to determine whether or when it is appropriate to revisit the review to incorporate new findings. We outline a vision for regularly updated reviews, known as ‘living’ systematic reviews, which are continually updated, with new evidence being identified and incorporated as soon as it becomes available.

While evidence surveillance and living systematic reviews may require some modifications to review processes, and can dramatically improve the delivery time and currency of updates, they are still essentially following a retrospective model of reviewing the existing evidence base. The retrospective nature of most systematic reviews poses an inevitable challenge, in that the selection of what types of evidence to include may be influenced by authors’ knowledge of the context and findings of the available studies. This might introduce bias into any aspect of the review’s eligibility criteria including the selection of a target population, the nature of the intervention(s), choice of comparator and the outcomes to be assessed. The best way to overcome this problem is to identify evidence entirely prospectively, that is before the results of the studies are known. Section 22.3 describes such prospectively planned meta-analyses.

Finally, Section 22.4 addresses concerns about the regular repeating of statistical tests in meta-analyses as they are updated over time. Cochrane actively discourages use of the notion of statistical significance in favour of reporting estimates and confidence intervals, so such concerns should not arise. Nevertheless, sequential approaches are an established method in randomized trials, and may play a role in a prospectively planned series of trials in a prospective meta-analysis.

22.2 Evidence surveillance: active monitoring of the accumulating evidence

22.2.1 Maintaining the currency of systematic reviews

Cochrane Reviews were conceived with the vision that they be kept up to date. For many years, a policy was in place of updating each Cochrane Review at least every two years. This policy was not closely followed due to a range of issues including: a lack of resources; the need to balance starting new reviews with maintaining older ones; the rapidly growing volume of research in some areas of health care and the paucity of new evidence in others; and challenges in knowing at any given point in time whether a systematic review was out of date and therefore possibly giving misleading, and potentially harmful, advice.

Maintaining the currency of systematic reviews by incorporating new evidence is important in many cases. For example, one study suggested that while the conclusions of most reviews might be valid for five or more years, the findings of 23% might be out of date within two years, and 7% were outdated at the time of their publication (Shojania et al 2007). Systematic reviews in rapidly evolving fields are particularly at risk of becoming out of date, leading to the development of a range of methods for identifying when a systematic review might need to be updated.

22.2.2 Signals for updating

Strategies for prioritizing updates, and for updating only reviews that warrant it, have been developed (Martínez García et al 2017) (see Chapter 2, Section 2.4.1). A multi-component tool was proposed by Takwoingi and colleagues in 2013 (Takwoingi et al 2013). Garner and colleagues have refined this tool and described a staged process that starts by assessing the extent to which the review is up to date (including relevance of the question, impact of the review and implementation of appropriate and up-to-date methods), then examines whether relevant new evidence or new systematic review methodology are available, and then assesses the potential impact of updating the review in terms of whether the findings are likely to change (Garner et al 2016). For a detailed discussion of updating Cochrane Reviews, see online Chapter IV.

Information about the availability of new (or newly identified) evidence may come from a variety of sources and use a diverse range of approaches (Garner et al 2016), including:

- re-running the full search strategies in the original review;

- using an abbreviated search strategy;

- using literature notification services;

- developing machine-learning algorithms based on study reports identified for the original review;

- tracking studies in clinical trials (and other) registries;

- checking studies included in related systematic reviews; and

- other formal surveillance methods.

Searches of bibliographic databases may be streamlined by using literature notification services (‘alerts’), whereby searches are run automatically at regular intervals, with potentially relevant new research being provided (‘pushed’) to the review authors (see Chapter 4, Section 4.4.9). Alternatively, it may be possible to run automated searches via an application programming interface (API). Unfortunately, only some databases offer notification services and, of those that do not, only some offer an open API that allows review authors to set up their own automated searches. Thus, this approach is most useful when the studies likely to be relevant to the review are those indexed in systems that will work within a ‘push’ model (typically, large mainstream biomedical databases such as MEDLINE). A further key challenge, which is lessening over time, is that trials and other registries, websites and other unpublished sources typically require manual searches, so it is inappropriate to rely entirely on ‘push’ services to identify all new evidence. See Section 22.2.4 for further information on technological approaches to ameliorate this.

Statistical methods have been proposed to assess the extent to which new evidence might affect the findings of a systematic review. Sample size calculations can incorporate the result of a current meta-analysis, thus providing information about how additional studies of a particular sample size could have an impact on the results of an updated meta-analysis (Sutton et al 2007, Roloff et al 2013). These methods demonstrate in many cases that new evidence may have very little impact on a random-effects meta-analysis if there is heterogeneity across studies, and they require assumptions that the future studies will be similar to the existing studies. Their practical use in deciding whether to update a systematic review may therefore be limited.

As part of their development of the aforementioned tool, Takwoingi and colleagues created a prediction equation based on findings from a sample of 65 updated Cochrane Reviews (Takwoingi et al 2013). They collated a list of numerical ‘signals’ as candidate predictors of changing conclusions on updating (including, for example, heterogeneity statistics in the original meta-analysis, presence of a large new study, and various measures of the amount of information in the new studies versus the original meta-analysis). Their prediction equation involved two of these signals: the ratio of statistical information (inverse variance) in the new versus the original studies, and the number of new studies. Further work is required to develop ways to operationalize this approach efficiently, as it requires detailed knowledge of the new evidence; once this is in place, much of the effort to perform the update has already been expended.

22.2.3 ‘Living’ systematic reviews

A ‘living’ systematic review (LSR) is a systematic review that is continually updated, with new (or newly identified) evidence incorporated as soon as it becomes available (Elliott et al 2014, Elliott et al 2017). Such regular and frequent updating has been suggested for reviews of high priority to decision makers, when certainty in the existing evidence is low or very low, and when there is likely to be new research evidence (Elliott et al 2017).

Continual surveillance for new research evidence is undertaken by frequent searches (e.g. monthly), and new information is incorporated into the review in a timely manner (e.g. within a month of its identification). Ongoing developments in technology, which we overview in Section 22.2.4. An important issue when setting up an LSR is that the search methods and anticipated frequency of review updates are made explicit in the review protocol. This transparency is helpful for end-users, giving them the opportunity to plan downstream decisions around the expected dates of new versions, and reducing the need for others to plan or undertake review updates. The maintenance of LSRs offers the possibility for decision makers to update their processes in line with evidence updates from the LSR; for example, facilitating ‘living’ guidelines (Akl et al 2017), although ongoing challenges include the clear communication to authors, editors and users on what has changed when evidence is updated, and how to implement frequently updated guidelines. Practical guidance on initiating and maintaining LSRs has been developed by the Living Evidence Network.

22.2.4 Technologies to support evidence surveillance

Moving towards more regular updates of reviews may yield benefits in terms of their currency (Elliott et al 2014), but streamlining the necessary increase in searching is required if they are not to consume more resources than traditional approaches. Fortunately, new developments in information and computer science offer some potential for reductions in manual effort through automation. (For an overview of a range of these technologies see Chapter 4, Section 4.6.6.2.)

New systems (such as the Epistemonikos database, which contains the results of regular searches of multiple datasets), offer potential reductions in the number of databases that individuals need to search, as well as reducing duplication of effort across review teams. In addition, the growth in interest of open access publications has led to the creation of large datasets of open access bibliographic records, such as OpenCitation, CrossRef and Microsoft Academic. As these datasets continue to grow to contain all relevant records in their respective areas, they may also reduce the need for author teams to search as many different sources as they currently need to.

Undertaking regular searches also requires the regular screening of records retrieved for eligibility. Once the review has been set up and initial searches screened, subsequent updates can reduce manual screening effort using automation tools that ‘learn’ the review’s eligibility criteria based on previous screening decisions by the review authors. Automation tools that are built on large numbers of records for more generic use are also available, such as Cochrane’s RCT Classifier, which can be used to filter studies that are unlikely to be randomized trials from a set of records (Thomas et al 2017). Cochrane has also developed Cochrane Crowd, which crowdsources decisions classifying studies as randomized trials, (see Chapter 4, Section 4.6.6.2).

Later stages of the review process can also be assisted using new technologies. These include risk-of-bias assessment, the extraction of structured data from tables in PDF files, information extraction from reports (such as identifying the number of participants in a study and characteristics of the intervention) and even the writing of review results. These technologies are less well-advanced than those used for study identification.

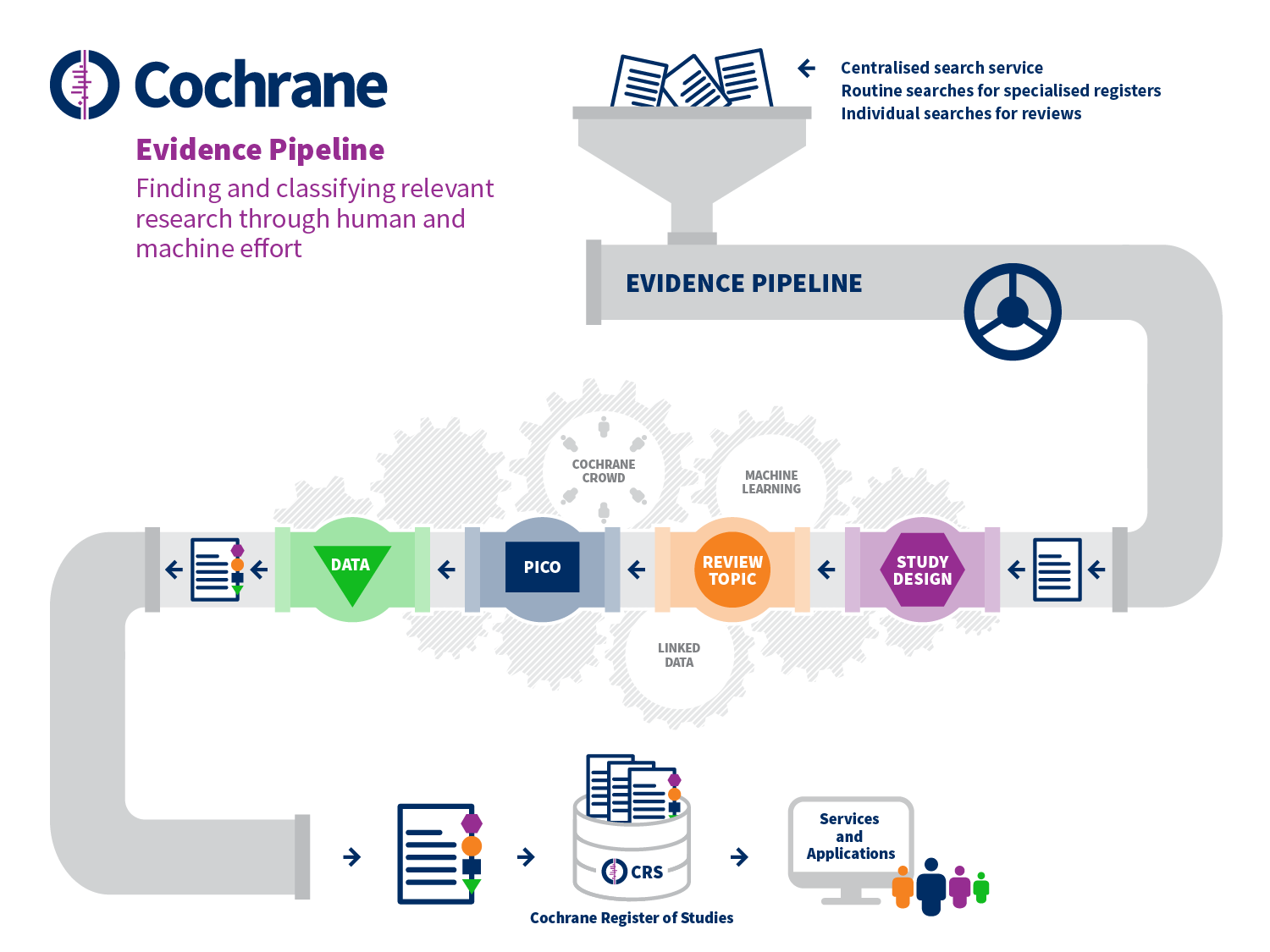

These various tools aim to reduce manual effort at specific points in the standard systematic review process. However, Cochrane is also setting up systems that aim to change the study selection process quite substantially, as depicted in Figure 22.2.a. These developments begin with the prospective identification of relevant evidence, outside of the context of any given review, including bibliographic and trial registry records, through centralized routine searches of appropriate sources. These records flow through a ‘pipeline’ which classifies the records in detail using a combination of machine learning and human effort (including Cochrane Crowd). First, the type of study is determined and, if it is likely to be a randomized trial, then the record proceeds to be classified in terms of its review topic and its PICO elements using terms from the Cochrane Linked Data ontology. Finally, relevant data are extracted from the full text report. The viability of such a system depends upon its accuracy, which is contingent on human decisions being consistent and correct. For this reason, the early focus on randomized trials is appropriate, as a clear and widely understood definition exists for this type of study. Overall, the accuracy of Cochrane Crowd for identification of randomized trials exceeds 99%; and the machine learning system is similarly calibrated to achieve over 99% recall (Wallace et al 2017, Marshall et al 2018).

Setting up such a system for centralized study discovery is yielding benefits through economies of scale. For example, in the past the same decisions about the same studies have been made multiple times across different reviews because previously there was no way of sharing these decisions between reviews. Duplication in manual effort is being reduced substantially by ensuring that decisions made about a given record (e.g. whether or not it describes a randomized trial) are only made once. These decisions are then reflected in the inclusion of studies in the Cochrane Register of Studies, which can then be searched more efficiently for future reviews. The system benefits further from its scale by learning that if a record is relevant for one review, it is unlikely to be relevant for reviews with quite different eligibility criteria. Ultimately, the aim is for randomized trials to be identified for reviews through a single search of their PICO classifications in the central database, with new studies for existing reviews being identified automatically.

Figure 22.2.a Evidence Pipeline

22.3 Prospectively planned meta-analysis

22.3.1 What is a prospective meta-analysis?

A properly conducted systematic review defines the question to be addressed in advance of the identification of potentially eligible trials. Systematic reviews are by nature, however, retrospective because the trials included are usually identified after the trials have been completed and the results reported. A prospective meta-analysis (PMA) is a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that are identified, evaluated and determined to be eligible for the meta-analysis before the relevant results of any of those studies become known. Most experience of PMA comes from their application to randomized trials. In this section we focus on PMAs of trials, although most of the same considerations will also apply to systematic reviews of other types of studies.

PMA can help to overcome some of the problems of retrospective meta-analyses of individual participant data or of aggregate data by enabling:

- hypotheses to be specified without prior knowledge of the results of individual trials (including hypotheses underlying subgroup analyses);

- selection criteria to be applied to trials prospectively; and

- analysis methods to be chosen before the results of individual trials are known, avoiding potential difficulties in interpretation arising from data-dependent decisions.

PMAs are usually initiated when trials have already started recruiting, and are carried out by collaborative groups including representatives from each of the participating trials. They have tended to involve collecting individual participant data (IPD), such that they have many features in common with retrospective IPD meta-analyses (see also Chapter 26).

If initiated early enough, PMA provides an opportunity for trial design, data collection and other trial processes to be standardized across the eligible ongoing trials. For example, the investigators may agree to use the same instrument to measure a particular outcome, and to measure the outcome at the same time-points in each trial. In a Cochrane Review of interventions for preventing obesity in children, for example, the diversity and unreliability of some of the outcome measures made it difficult to combine data across trials (Summerbell et al 2005). A PMA of this question proposed a set of shared standards so that some of the issues raised by lack of standardization could be addressed (Steinbeck et al 2006).

PMAs based on IPD have been conducted by trialists in cardiovascular disease (Simes 1995, WHO-ISI Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration 1998), childhood leukaemia (Shuster and Gieser 1996, Valsecchi and Masera 1996), childhood and adolescent obesity (Steinbeck et al 2006, Askie et al 2010) and neonatology (Askie et al 2018). There are areas such as infectious diseases, however, where the opportunity to use PMA has largely been missed (Ioannidis and Lau 1999).

Where resources are limited, it may still be possible to undertake a prospective systematic review and meta-analysis based on aggregate data, rather than IPD, as we discuss in Section 22.3.6. In practice, these are often initiated at a later stage during the course of the trials, so there is less opportunity to standardize conduct of the trials. However, it is possible to harmonize data for inclusion in meta-analysis.

22.3.1.1 What is the difference between a prospective meta-analysis and a large multicentre trial?

PMAs based on IPD are similar to multicentre clinical trials and have similar advantages, including increased sample size, increased diversity of treatment settings and populations, and the ability to examine heterogeneity of intervention effects across multiple settings. However, whereas traditional multicentre trials implement a single protocol across all sites to reduce variability in trial conduct among centres, PMAs allow investigators greater flexibility in how their trial is conducted. Sites can follow a local protocol appropriate to local circumstances, with the local protocol being aligned with elements of a PMA protocol that are common to all included trials.

PMAs may be an attractive alternative when a single, adequately sized trial is infeasible for practical or political reasons (Simes 1987, Probstfield and Applegate 1998). They may also be useful when two or more trials addressing the same question are started with the investigators ignorant of the existence of the other trial(s): once these similar trials are identified, investigators can plan prospectively to combine their results in a meta-analysis.

Variety in the design of the included trials is a potentially desirable feature of PMA as it may improve generalizability. For example, FICSIT (Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques) was a pre-planned meta-analysis of eight trials of exercise-based interventions in a frail elderly population (Schechtman and Ory 2001). The eight FICSIT sites defined their own interventions using site-specific endpoints and evaluations and differing entry criteria (except that all participants were elderly).

22.3.1.2 Negotiating collaboration

As with retrospective IPD meta-analyses, negotiating and establishing a strong collaboration with the participating trialists is essential to the success of a PMA (see Chapter 26, Sections 26.1.3 and 26.2.1). The collaboration usually has a steering group or secretariat that manages the project on a day-to-day basis. Because the collaboration must be formed before the results of any trial are known, an important focus of a PMA’s collaborative efforts is often on reaching agreement on trial population, design and data collection methods for each of the participating trials. Ideally, the collaborative group will agree on a core common protocol and data items (including operational definitions) that will be collected across all trials. While individual trials can include local protocol amendments or additional data items, the investigators should ensure that these will not compromise the core common protocol elements.

It is advisable for the collaborative group to obtain an explicit (and signed) collaboration agreement from each of the trial groups. This should also encourage substantive contributions by the individual investigators, ensure ‘buy-in’ to the concept of the PMA, and facilitate input into the protocol.

22.3.1.3 Confidentiality of individual participant data and results

Confidentiality issues regarding data anonymity and security are similar to those for IPD meta-analyses (see Chapter 26, Section 26.2.4). Specific issues for PMA include planning how to deal with trials as they reach completion and publish their results, and how to manage issues relating to data and safety monitoring, including the impact of interim analyses of individual trials in the PMA, or possibly a pooled interim analysis of the PMA (see also Section 22.3.5).

22.3.2 Writing a protocol for a prospective meta-analysis

All PMAs should be registered on PROSPERO or a similar registry, and have a publicly available protocol. For an example protocol, see the NeOProM Collaboration protocol (Askie et al 2011). Developing a protocol for a PMA is conceptually similar to the process for a systematic review with a traditional meta-analysis component (Moher et al 2015). However, some considerations are unique to a PMA, as follows.

Objectives, eligibility and outcomes As for any systematic review or meta-analysis, the protocol for a PMA should specify its objectives and eligibility criteria for inclusion of the trials (including trial design, participants, interventions and comparators). In addition, it should specify which outcomes will be measured by all trials in the PMA, and when and how these should be measured. Additionally, details of subgroup analysis variables should be specified.

Search methods Just as for a retrospective systematic review, a systematic search should be performed to identify all eligible ongoing trials, in order to maximize precision. The protocol should describe in detail the efforts made to identify ongoing, or planned trials, or to identify trialists with a common interest in developing a PMA, including how potential collaborators have been (or will be) located and approached to participate.

Trial details Details of trials already identified for inclusion should be listed in the protocol, including their trial registration identifiers, the anticipated number of participants and timelines for each participating trial. The protocol should state whether a signed agreement to collaborate has been obtained from the appropriate representative of each trial (e.g. the sponsor or principal investigator). The protocol should include a statement that, at the time of inclusion in the PMA, no trial results related to the PMA research question were known to anyone outside each trial’s own data monitoring committee. If eligible trials are identified but not included in the PMA because their results related to the PMA research question are already known, the PMA protocol should outline how these data will be dealt with. For example, sensitivity analyses including data from these trials might be planned. The protocol should describe actions to be taken if subsequent trials are located while the PMA is in progress.

Data collection and analysis The protocol should outline the plans for the collection and analyses of data in a similar manner to that of a standard, aggregate data meta-analysis or an IPD meta-analysis. Details of overall sample size and power calculations, interim analyses (if applicable) and subgroup analyses should be provided. For a prospectively planned series of trials, a sequential approach to the meta-analysis may be reasonable (see Section 22.4).

In an IPD-PMA, the protocol should describe what will happen if the investigators of some trials within the PMA are unable (or unwilling) to provide participant-level data. Would the PMA secretariat, for example, accept appropriate summary data? The protocol should specify whether there is an intention to update the PMA data at regular intervals via ongoing cycles of data collection (e.g. five yearly). A detailed statistical analysis plan should be agreed and made public before the receipt or analysis of any data to be included in the PMA.

Management and co-ordination The PMA protocol should outline details of project management structure (including any committees, see Section 22.3.1.2), the procedures for data management (how data are to be collected, the format required, when data will be required to be submitted, quality assurance procedures, etc; see Chapter 26, Section 26.2), and who will be responsible for the statistical analyses.

Publication policy It is important to have an authorship policy in place for the PMA (e.g. specifying that publications will be in the group name, but also including a list of individual authors), and a policy on manuscript preparation (e.g. formation of a writing committee, opportunities to comment on draft papers).

A unique issue that arises within the context of the PMA (which would generally not arise for a multicentre trial or a retrospective IPD meta-analysis) is whether or not individual trials should publish their own results separately and, if so, the timing of those publications. In addition to contributing to the PMA, it is likely that investigators will prefer trial-specific publications to appear before the combined PMA results are published. It is recommended that PMA publication(s) clearly indicate the sources of the included data and refer to prior publications of the individual included trials.

22.3.3 Data collection in a prospective meta-analysis

Participating trials in a PMA usually agree to supply individual participant data once their individual trials are completed and published. As trialists prospectively decide which data they will collect and in what format, the need to re-define and re-code supplied data should be less problematic than is often the case with a retrospective IPD meta-analysis.

Once data are received by the PMA secretariat, they should be rigorously checked using the same procedures as for IPD meta-analyses, including checking for missing or duplicated data, conducting data plausibility checks, assessing patterns of randomization, and ensuring the information supplied is up to date (see Chapter 26, Section 26.3). Data queries will be resolved by direct consultation with the individual trialists before being included in the final combined dataset for analysis.

22.3.4 Data analysis in prospective meta-analysis

Most PMAs will use similar analysis methods to those employed in retrospective IPD meta-analyses (see Chapter 26, Section 26.4). The use of participant-level data also permits more statistically powerful investigations of whether intervention effects vary according to participant characteristics, and in some cases allow prognostic modelling.

22.3.5 Interim analysis and data monitoring in prospective meta-analysis

Individual clinical trials frequently include a plan for interim analyses of data, particularly to monitor safety of the interventions. PMA offers a unique opportunity to perform these interim analyses using data contributed by all trials. Under the auspices of an over-arching data safety monitoring committee (DSMC) for the PMA, available data may be combined from all trials for an interim analysis, or assessed separately by each trial and the results then shared amongst the DSMCs of all the participating trials.

The ability to perform combined interim analyses raises some ethical issues. Is it, for example, appropriate to continue randomization within individual trials if an overall net benefit of an intervention has been demonstrated in the combined analysis? When results are not known in the subgroups of clinical interest, or for less common endpoints, should the investigators continue to proceed with the PMA to obtain further information regarding overall net clinical benefit? If each trial has its own DSMC, then communication amongst committees would be beneficial in this situation, as recommended by Hillman and Louis (Hillman and Louis 2003). This would be helpful, for example, in deciding whether or not to close an individual trial early because of evidence of efficacy from the combined interim data. It could be argued that knowledge of emerging, concerning, combined safety data from all participating trials might actually reduce the chances of spurious early stopping of an individual trial. It would be helpful, therefore, for the individual trial DSMCs within the PMA to adopt a common agreement that individual trials should not be stopped until the aims of the PMA, with respect to subgroups and uncommon endpoints (or ‘net clinical benefit’), are achieved.

Another possible option might be to consider limiting enrolment in the continuing trials to participants in a particular subgroup of interest if such a decision makes clinical and statistical sense. In any case, it might be appropriate to apply the concepts of sequential meta-analysis methodology, as discussed in Section 22.4, to derive stringent stopping rules for the PMA as individual trial results become available.

22.3.6 Prospective approaches based on aggregate data: the Framework for Adaptive Meta-analysis (FAME)

The Framework for Adaptive Meta-analysis (FAME) is a combination of ‘traditional’ and prospective elements that is suitable for aggregate data (rather than IPD) meta-analysis and is responsive to emerging trial results. In the FAME approach, all methods are defined in a publicly available systematic review protocol ideally before all trial results are known. The approach aims to take all eligible trials into account, including those that have been completed (and analysed) and those that are yet to complete or report (Tierney et al 2017). FAME can be used to anticipate the earliest opportunity for a reliable aggregate data meta-analysis, which may be well in advance of all relevant results becoming available. The key steps of FAME are as follows.

1) Start the systematic review process whilst most trials are ongoing or yet to report

This makes it possible to plan the objectives, eligibility criteria, outcomes and analyses with little or no knowledge of eligible trial results, and also to anticipate the emergence of trial results so that completion of the review and meta-analysis can be aligned accordingly.

2) Search comprehensively for published, unpublished and ongoing eligible trials

This ensures that the meta-analysis planning is based on all potential trial data and that results can be placed in the context of all the current and likely future evidence. Conference proceedings, study registers and investigator networks are therefore important sources of information. Although unpublished and ongoing studies should be examined for any systematic review, evidence suggests that it is not standard practice (Page et al 2016).

3) Liaise with trialists to develop and maintain a detailed understanding of these trials

Liaising with trialists provides information on how trials are progressing and when results are likely to be available, but it also provides information on trial design, conduct and analysis, bringing greater clarity to eligibility screening and accuracy to risk-of-bias assessments (Vale et al 2013).

4) Predict if and when sufficient results will be available for reliable and robust meta-analysis (typically using aggregate data)

The information from steps 2 and 3 about how results will emerge over time allows a prospective assessment of the feasibility and timing of a reliable meta-analysis. A first indicator of reliability is that the projected amount of participants or events that would be available for the meta-analysis constitute an ‘optimal information size’ (Pogue and Yusuf 1997). In other words they would provide sufficient power to detect realistic effects of the intervention under investigation, on the basis of standard methods of sample size calculation. A second indicator of reliability is that the anticipated participants or events would comprise a substantial proportion of the total eligible (‘relative information size’). This serves to minimize the likelihood of reporting or other data availability biases. Such predictions and decisions for FAME should be outlined in the systematic review protocol.

5) Conduct meta-analysis and interpret results, taking account of available and unavailable data

Interpretation should consider how representative the actual data obtained are, and the potential impact of the results of unpublished or ongoing trials that were not included. This is in addition to the direction and precision of the meta-analysis result and consistency of effects across trials, as is standard.

6) Assess the value of updating the systematic review and meta-analysis in the future

If the results of a meta-analysis are not deemed definitive, it is important to ascertain whether there is likely to be value in updating with trial results that will emerge in the future and, if so, whether aggregate data will suffice or IPD might be needed.

FAME has been used to evaluate reliably the effects of prostate cancer interventions well in advance of all trial results being available (Vale et al 2016, Rydzewska et al 2017). In these reviews, collaboration with trial investigators provided access to pre-publication results, expediting the review process further and allowing publication in the same time frame as key trial results, increasing the visibility and potential impact of both. It also enabled access to additional outcome, subgroup and toxicity analyses, which allowed a more consistent and thorough analysis than is often possible with aggregate data. Such an approach requires a suitable non-disclosure agreement between the review authors and the trial authors.

Additionally, FAME could be used in the living systematic review context (Crequit et al 2016, Elliott et al 2017, Nikolakopoulou et al 2018), either to provide a suitable baseline meta-analysis, or to predict when a living update might be definitive. Combining multiple FAME reviews in a network meta-analysis (Vale et al 2018) offers an alternative to living network meta-analysis for the timely synthesis of competing treatments (Crequit et al 2016, Nikolakopoulou et al 2018).

22.4 Statistical analysis of accumulating evidence

22.4.1 Statistical issues arising from repeating meta-analyses

In any prospective or updated systematic review the body of evidence may grow over time, and meta-analyses may be repeated with the addition of new studies. If each meta-analysis is interpreted through the use of a statistical test of significance (e.g. categorizing a finding as ‘statistically significant’ if the P value is less than 0.05 or ‘not statistically significant’ otherwise), then on each occasion the conclusion has a 5% chance of being incorrect if the null hypothesis (that there is no difference between experimental and comparator interventions on average) is true. Such an incorrect conclusion is often called a type I error. If significance tests are repeated each time a meta-analysis is updated with new studies, then the probability that at least one of the repeated meta-analyses will produce a P value lower than 0.05 under the null hypothesis (i.e. the probability of a type I error) is somewhat higher than 5% (Berkey et al 1996). This has led some researchers to be concerned about the statistical methods they were using when meta-analyses are repeated over time, for fear they were leading to spurious findings.

A related concern is that we may wish to determine when there is enough evidence in the meta-analysis to be able to say that the question is sufficiently well-answered. Traditionally, ‘enough evidence’ has been interpreted as information with enough statistical power (e.g. 80% or 90% power) to detect a specific magnitude of effect using a significance test. This requires that attention be paid to type II error, which is the chance that a true (non-null) effect will fail to be picked up by the test. When meta-analyses are repeated over time, statistical power may be expected to increase as new studies are added. However, just as type I error is not controlled across repeated analyses, neither is type II error.

Statistical methods for meta-analysis have been proposed to address these concerns. They are known as sequential approaches, and are derived from methods commonly used in clinical trials. The appropriateness of applying sequential methods in the context of a systematic review has been hotly debated. We describe the main methods in brief in Section 22.4.2, and in Section 22.4.3 we explain that the use of sequential methods is explicitly discouraged in the context of a Cochrane Review, but may be reasonable in the context of a PMA.

22.4.2 Sequential statistical methods for meta-analysis

Interim analyses are often performed in randomized trials, so the trial can be stopped early if there is convincing evidence that the intervention is beneficial or harmful. Sequential methods have been developed that aim to control type I and II errors in the context of a clinical trial. These methods have been adapted for prospectively adding studies to a meta-analysis, rather than prospectively adding participants to a trial.

The main methods involve pre-specification of a stopping rule. The stopping rule is informed by considerations of (i) type I error; (ii) type II error; (c) a clinically important magnitude of effect; and (iv) the desired properties of the stopping rule (e.g. whether it is particularly important to avoid stopping too soon). To control type II error, it is necessary to quantify the amount of information that has accumulated to date. This can be measured using sample size (number of participants) or using statistical information (i.e. the sum of the inverse-variance weights in the meta-analysis).

Implementation of the stopping rule can be done in several ways. One possibility is to perform a statistical test in the usual way but to lower the threshold for interpreting the result as statistically significant. This penalization of the type I error rate at each analysis may be viewed as ‘spending’ (or distributing) proportions of the error over the repeated analyses. The amount of penalization is specified to create the stopping rule, and is referred to as an ‘alpha spending function’ (because alpha is often used as shorthand for the acceptable type I error rate).

An alternative way of implementing a stopping rule is to plot the path of the accumulating evidence. Specifically, the plot is a scatter plot of a cumulative measure of effect magnitude (one convenient option is the sum of the study effect estimates times their meta-analytic weights) against a cumulative measure of statistical information (a convenient option is the sum of the meta-analytic weights) at each update. The plotted points are compared with a plot ‘boundary’, which is determined uniquely by the four pre-specified considerations of a stopping rule noted above. A conclusive result is deemed to be achieved if a point in the plot falls outside the boundary. For meta-analysis, a rectangular boundary has been recommended, as this reduces the chance of crossing a boundary very early; this also produces a scheme that is equivalent to the most popular alpha-spending approach proposed by O’Brien and Fleming (O'Brien and Fleming 1979). Additional stopping boundaries can be added to test for futility, so the updating process can be stopped if it is unlikely that a meaningful effect will be found.

Methods translate directly from sequential clinical trials to a sequential fixed-effect meta-analysis. Random-effects meta-analyses are more problematic. For sequential methods based on statistical weights, the between-study variation (heterogeneity) is naturally incorporated. For methods based on sample size, adjustments can be made to the target sample size to reflect the impact of between-study variation. Either way, there are important technical problems with the methods because between-study variation impacts on the results of a random-effects meta-analysis and it is impossible to anticipate how much between-study variation there will be in the accumulating evidence. Whereas it would be natural to expect that adding studies to a meta-analysis increases precision, this is not necessarily the case under a random-effects model. Specifically, if a new set of studies is added to a meta-analysis among which there is substantially more heterogeneity than in the previous studies, then the estimated between-study variance will go up, and the confidence interval for the new totality of studies may get wider rather than narrower. Possibilities to reduce the impact of this include: (i) using a fixed value (a prior guess) for the amount of between-study heterogeneity throughout the sequential scheme; and (ii) using a high estimate of the amount of heterogeneity during the early stages of the sequential scheme.

Sequential approaches can be inverted to produce a series of confidence intervals, one for each update, which reflects the sequential scheme. This allows representation of the results in a conventional forest plot. The interpretation of these confidence intervals is that we can be 95% confident that all confidence intervals in the entire series of adjusted confidence intervals (across all updates) contain the true intervention effect. The adjusted confidence interval excludes the null value only if a stopping boundary is crossed. This is a somewhat technical interpretation that is unlikely to be helpful in the interpretation of results within any particular update of a review.

There are several choices to make when deciding on a sequential approach to meta-analysis. Two particular sets of choices have been articulated in papers by Wetterslev, Thorlund, Brok and colleagues, and by Whitehead, Higgins and colleagues.

The first group refer to their methods as ‘trials sequential analysis’ (TSA). They use the principle of alpha spending and articulate the desirable total amount of information in terms of sample size (Wetterslev et al 2008, Brok et al 2009, Thorlund et al 2009). This sample size is calculated in the same way as if the meta-analysis was a single clinical trial, by setting a desired type I error, an assumed effect size, and the desired statistical power to detect that effect. They recommended that the sample size be adjusted for heterogeneity, using either some pre-specified estimate of heterogeneity or the best current estimate of heterogeneity in the meta-analysis. The adjustment is generally made using a statistic called D2, which produces a larger required sample size, although the more widely used I2 statistic may be used instead (Wetterslev et al 2009).

Whitehead and Higgins implemented a boundaries approach and represent information using statistical information (specifically, the sum of the meta-analytic weights) (Whitehead 1997, Higgins et al 2011). As noted, this implicitly adjusts for heterogeneity because as heterogeneity increases, the information contained in the meta-analysis decreases. In this approach, the cumulative information can decrease between updates as well as increase (i.e. the path can go backwards in relation to the boundary). These authors propose a parallel Bayesian approach to updating the estimate of between-study heterogeneity, starting with an informative prior distribution, to reduce the risk that the path will go backwards (Higgins et al 2011). If the prior estimate of heterogeneity is suitably large, the method can account for underestimation of heterogeneity early in the updating process.

22.4.3 Using sequential approaches to meta-analysis in Cochrane Reviews

Formal sequential meta-analysis approaches are discouraged for updated meta-analyses in most circumstances within the Cochrane context. They should not be used for the main analyses, or to draw main conclusions. This is for the following reasons.

-

The results of each meta-analysis, conducted at any point in time, indicate the current best evidence of the estimated intervention effect and its accompanying uncertainty. These results need to stand on their own merit. Decision makers should use the currently available evidence, and their decisions should not be influenced by previous meta-analyses or plans for future updates.

-

Cochrane Review authors should interpret evidence on the basis of the estimated magnitude of the effect of intervention and its uncertainty (usually quantified using a confidence interval) and not on the basis of statistical significance (see Chapter 15, Section 15.3.1). In particular, Cochrane Review authors should not draw binary interpretations of intervention effects as present or absent, based on defining results as ‘significant’ or ‘non-significant’ (see Chapter 15, Section 15.3.2).

-

There are important differences between the context of an individual trial and the context of a meta-analysis. Whereas a trialist is in control of recruitment of further participants, the meta-analyst (except in the context of a prospective meta-analysis) has no control over designing or affecting trials that are eligible for the meta-analysis, so it would be impossible to construct a set of workable stopping rules which require a pre-planned set of interim analyses. Conversely, planned adjustments for future updates may be unnecessary if new evidence does not appear.

-

A meta-analysis will not usually relate to a single decision or single decision maker, so that a sequential adjustment will not capture the complexity of the decision making process. Furthermore, Cochrane summarizes evidence for the benefit of multiple end users including patients, health professionals, policy decision makers and guideline developers. Different decision makers may choose to use the evidence differently and reach different decisions based on different priorities and contexts. They might not agree with sequential adjustments or stopping rules set up by review authors.

- Heterogeneity is prevalent in meta-analyses and random-effects models are commonly used when heterogeneity is present. Sequential methods have important methodological limitations when heterogeneity is present.

It remains important for review authors to avoid over-optimistic conclusions being drawn from a small number of studies. Review authors need to be particularly careful not to over-interpret promising findings when there is very little evidence. Such findings could be due to chance, to bias, or to use of meta-analytic methods that have poor properties when there are few studies (see Chapter 10, Section 10.10.4), and might be overturned at later updates of the review. Evaluating the confidence in the body of evidence, for example using the GRADE framework, should highlight when there is insufficient information (i.e. too much imprecision) for firm conclusions to be drawn.

Sequential approaches to meta-analysis may be used in Cochrane Reviews in two situations.

1. Sequential methods may be used in the context of a prospectively planned series of clinical trials, when the primary analysis is a meta-analysis of the findings across trials, as discussed in Section 22.3. In this case, the meta-analysts are in control of the production of new data and crossing a boundary in a sequential scheme would indicate that no further data need to be collected.

2. Sequential methods may be performed as secondary analyses in Cochrane Reviews, to provide an additional interpretation of the data from a specific perspective. If sequential approaches are to be applied, then (i) they must be planned prospectively (and not retrospectively), with a full analysis plan provided in the protocol; and (ii) the assumptions underlying the sequential design must be clearly conveyed and justified, including the parameters determining the design such as the clinically important effect size, assumptions about heterogeneity, and both the type I and type II error rates.

22.5 Chapter information

Authors: James Thomas, Lisa M Askie, Jesse A Berlin, Julian H Elliott, Davina Ghersi, Mark Simmonds, Yemisi Takwoingi, Jayne F Tierney, Julian PT Higgins

Acknowledgements: The following contributed to the policy on use of sequential approaches to meta-analysis: Christopher Schmid, Stephen Senn, Jonathan Sterne, Elena Kulinskaya, Martin Posch, Kit Roes and Joanne McKenzie.

Funding: JFT’s work is funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MC_UU_12023/24). JT is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North Thames at Barts Health NHS Trust. JHE is supported by a Career Development Fellowship from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1126434). Development of Cochrane's Evidence Pipeline and RCT Classifier was supported by Cochrane's Game Changer Initiative and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council through a Partnership Project Grant (APP1114605). JPTH is a member of the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. JPTH received funding from National Institute for Health Research Senior Investigator award NF-SI-0617-10145. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

22.6 References

Akl EA, Meerpohl JJ, Elliott J, Kahale LA, Schunemann HJ, Living Systematic Review N. Living systematic reviews: 4. Living guideline recommendations. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2017; 91: 47-53.

Askie LM, Baur LA, Campbell K, Daniels L, Hesketh K, Magarey A, Mihrshahi S, Rissel C, Simes RJ, Taylor B, Taylor R, Voysey M, Wen LM, on behalf of the EPOCH Collaboration. The Early Prevention of Obesity in CHildren (EPOCH) Collaboration - an Individual Patient Data Prospective Meta-Analysis [study protocol]. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 728.

Askie LM, Brocklehurst P, Darlow BA, Finer N, Schmidt B, Tarnow-Mordi W. NeOProM: Neonatal Oxygenation Prospective Meta-analysis Collaboration study protocol. BMC Pediatrics 2011; 11: 6.

Askie LM, Darlow BA, Finer N, et al. Association between oxygen saturation targeting and death or disability in extremely preterm infants in the neonatal oxygenation prospective meta-analysis collaboration. JAMA 2018; 319: 2190-2201.

Berkey CS, Mosteller F, Lau J, Antman EM. Uncertainty of the time of first significance in random effects cumulative meta-analysis. Controlled Clinical Trials 1996; 17: 357-371.

Brok J, Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Apparently conclusive meta-analyses may be inconclusive--Trial sequential analysis adjustment of random error risk due to repetitive testing of accumulating data in apparently conclusive neonatal meta-analyses. International Journal of Epidemiology 2009; 38: 287-298.

Chalmers I. Electronic publications for updating controlled trial reviews. The Lancet 1986; 328: 287.

Crequit P, Trinquart L, Yavchitz A, Ravaud P. Wasted research when systematic reviews fail to provide a complete and up-to-date evidence synthesis: the example of lung cancer. BMC Medicine 2016; 14: 8.

Elliott JH, Turner T, Clavisi O, Thomas J, Higgins JPT, Mavergames C, Gruen RL. Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence-practice gap. PLoS Medicine 2014; 11: e1001603.

Elliott JH, Synnot A, Turner T, Simmonds M, Akl EA, McDonald S, Salanti G, Meerpohl J, MacLehose H, Hilton J, Tovey D, Shemilt I, Thomas J, Living Systematic Review N. Living systematic review: 1. Introduction-the why, what, when, and how. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2017; 91: 23-30.

Garner P, Hopewell S, Chandler J, MacLehose H, Schünemann HJ, Akl EA, Beyene J, Chang S, Churchill R, Dearness K, Guyatt G, Lefebvre C, Liles B, Marshall R, Martinez Garcia L, Mavergames C, Nasser M, Qaseem A, Sampson M, Soares-Weiser K, Takwoingi Y, Thabane L, Trivella M, Tugwell P, Welsh E, Wilson EC, Schünemann HJ, Panel for Updating Guidance for Systematic Reviews (PUGs). When and how to update systematic reviews: consensus and checklist. BMJ 2016; 354: i3507.

Higgins JPT, Whitehead A, Simmonds M. Sequential methods for random-effects meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine 2011; 30: 903-921.

Hillman DW, Louis TA. DSMB case study: decision making when a similar clinical trial is stopped early. Controlled Clinical Trials 2003; 24: 85-91.

Ioannidis JPA, Lau J. State of the evidence: current status and prospects of meta-analysis in infectious diseases. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1999; 29: 1178-1185.

Marshall IJ, Noel-Storr A, Kuiper J, Thomas J, Wallace BC. Machine learning for identifying Randomized Controlled Trials: An evaluation and practitioner's guide. Research Synthesis Methods 2018; 9: 602-614.

Martínez García L, Pardo-Hernandez H, Superchi C, Niño de Guzman E, Ballesteros M, Ibargoyen Roteta N, McFarlane E, Posso M, Roqué IFM, Rotaeche Del Campo R, Sanabria AJ, Selva A, Solà I, Vernooij RWM, Alonso-Coello P. Methodological systematic review identifies major limitations in prioritization processes for updating. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2017; 86: 11-24.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews 2015; 4: 1.

Nikolakopoulou A, Mavridis D, Furukawa TA, Cipriani A, Tricco AC, Straus SE, Siontis GCM, Egger M, Salanti G. Living network meta-analysis compared with pairwise meta-analysis in comparative effectiveness research: empirical study. BMJ 2018; 360: k585.

O'Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics 1979; 35: 549-556.

Page MJ, Shamseer L, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Sampson M, Tricco AC, Catalá-López F, Li L, Reid EK, Sarkis-Onofre R, Moher D. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews of biomedical research: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Medicine 2016; 13: e1002028.

Pogue JM, Yusuf S. Cumulating evidence from randomized trials: utilizing sequential monitoring boundaries for cumulative meta-analysis. Controlled Clinical Trials 1997; 18: 580-593; discussion 661-586.

Probstfield J, Applegate WB. Prospective meta-analysis: Ahoy! A clinical trial? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1998; 43: 452-453.

Roloff V, Higgins JPT, Sutton AJ. Planning future studies based on the conditional power of a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine 2013; 32: 11-24.

Rydzewska LHM, Burdett S, Vale CL, Clarke NW, Fizazi K, Kheoh T, Mason MD, Miladinovic B, James ND, Parmar MKB, Spears MR, Sweeney CJ, Sydes MR, Tran N, Tierney JF, STOPCaP Abiraterone Collaborators. Adding abiraterone to androgen deprivation therapy in men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cancer 2017; 84: 88-101.

Schechtman K, Ory M. The effects of exercise on the quality of life of frail older adults: a preplanned meta-analysis of the FICSIT trials. Annals of Behavioural Medicine 2001; 23: 186-197.

Shojania KG, Sampson M, Ansari MT, Ji J, Doucette S, Moher D. How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine 2007; 147: 224-233.

Shuster JJ, Gieser PW. Meta-analysis and prospective meta-analysis in childhood leukemia clinical research. Annals of Oncology 1996; 7: 1009-1014.

Simes RJ. Confronting publication bias: a cohort design for meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine 1987; 6: 11-29.

Simes RJ. Prospective meta-analysis of cholesterol-lowering studies: the Prospective Pravastatin Pooling (PPP) Project and the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaboration. American Journal of Cardiology 1995; 76: 122c-126c.

Steinbeck KS, Baur LA, Morris AM, Ghersi D. A proposed protocol for the development of a register of trials of weight management of childhood overweight and obesity. International Journal of Obesity 2006; 30: 2-5.

Summerbell CD, Waters E, Edmunds LD, Kelly S, Brown T, Campbell KJ. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. 3 ed2005.

Sutton AJ, Cooper NJ, Jones DR, Lambert PC, Thompson JR, Abrams KR. Evidence-based sample size calculations based upon updated meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine 2007; 26: 2479-2500.

Takwoingi Y, Hopewell S, Tovey D, Sutton AJ. A multicomponent decision tool for prioritising the updating of systematic reviews. BMJ 2013; 347: f7191.

Thomas J, Noel-Storr A, Marshall I, Wallace B, McDonald S, Mavergames C, Glasziou P, Shemilt I, Synnot A, Turner T, Elliott J, Living Systematic Review N. Living systematic reviews: 2. Combining human and machine effort. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2017; 91: 31-37.

Thorlund K, Devereaux PJ, Wetterslev J, Guyatt G, Ioannidis JPA, Thabane L, Gluud LL, Als-Nielsen B, Gluud C. Can trial sequential monitoring boundaries reduce spurious inferences from meta-analyses? International Journal of Epidemiology 2009; 38: 276-286.

Tierney J, Vale CL, Burdett S, Fisher D, Rydzewska L, Parmar MKB. Timely and reliable evaluation of the effects of interventions: a framework for adaptive meta-analysis (FAME). Trials 2017; 18.

Vale CL, Tierney JF, Burdett S. Can trial quality be reliably assessed from published reports of cancer trials: evaluation of risk of bias assessments in systematic reviews. BMJ 2013; 346: f1798.

Vale CL, Burdett S, Rydzewska LHM, Albiges L, Clarke NW, Fisher D, Fizazi K, Gravis G, James ND, Mason MD, Parmar MKB, Sweeney CJ, Sydes MR, Tombal B, Tierney JF, STOpCaP Steering Group. Addition of docetaxel or bisphosphonates to standard of care in men with localised or metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analyses of aggregate data. Lancet Oncology 2016; 17: 243-256.

Vale CL, Fisher DJ, White IR, Carpenter JR, Burdett S, Clarke NW, Fizazi K, Gravis G, James ND, Mason MD, Parmar MKB, Rydzewska LH, Sweeney CJ, Spears MR, Sydes MR, Tierney JF. What is the optimal systemic treatment of men with metastatic, hormone-naive prostate cancer? A STOPCAP systematic review and network meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology 2018; 29: 1249-1257.

Valsecchi MG, Masera G. A new challenge in clinical research in childhood ALL: the prospective meta-analysis strategy for intergroup collaboration. Annals of Oncology 1996; 7: 1005-1008.

Wallace BC, Noel-Storr A, Marshall IJ, Cohen AM, Smalheiser NR, Thomas J. Identifying reports of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) via a hybrid machine learning and crowdsourcing approach. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2017; 24: 1165-1168.

Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, Gluud C. Trial sequential analysis may establish when firm evidence is reached in cumulative meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2008; 61: 64-75.

Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, Gluud C. Estimating required information size by quantifying diversity in random-effects model meta-analyses. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2009; 9: 86.

Whitehead A. A prospectively planned cumulative meta-analysis applied to a series of concurrent clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine 1997; 16: 2901-2913.

WHO-ISI Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration. Protocol for prospective collaborative overviews of major randomised trials of blood-pressure-lowering treatments. Journal of Hypertension 1998; 16: 127-137.